The gravitational interaction between the Earth and the Moon causes one hemisphere of the Moon to always “stand still”, never facing the Earth. However, the Moon still rotates, it just takes the time to rotate once on its axis to complete one orbit around the Earth.

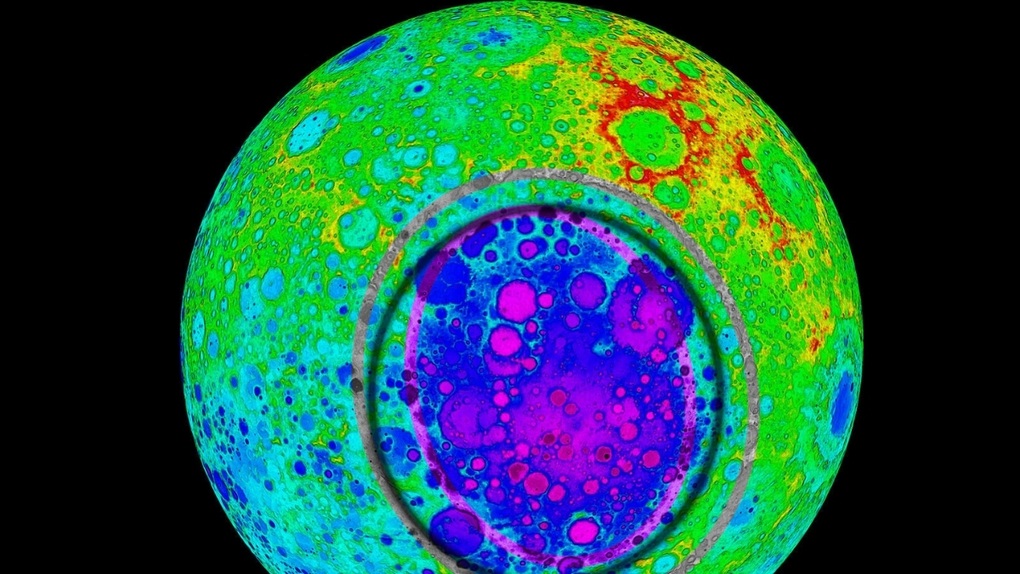

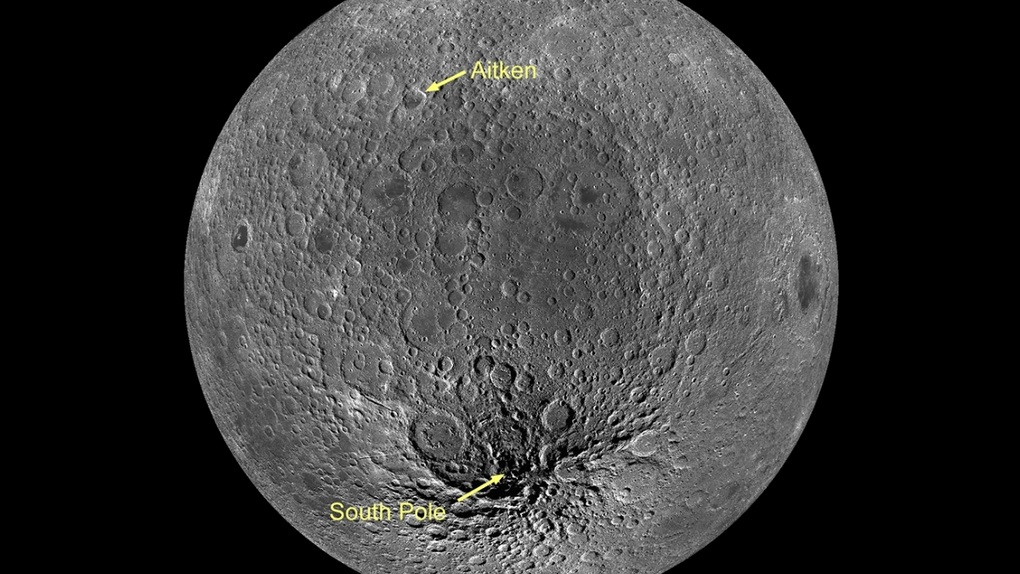

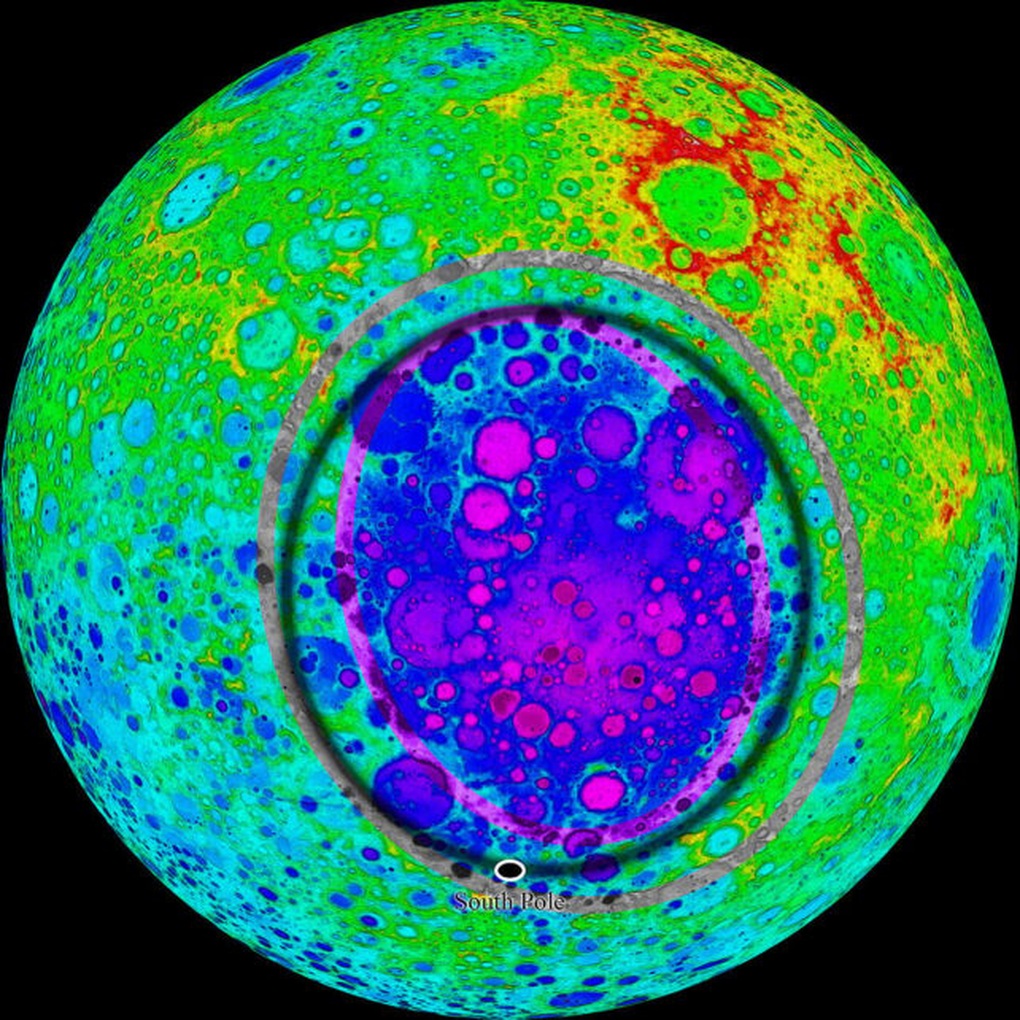

This phenomenon is called synchronous rotation, and on the far side of the Moon, there is a giant crater called the South Pole-Aitken basin, which stretches more than 1,930 km from north to south and 1,600 km from east to west.

This ancient impact crater formed about 4.3 billion years ago when an asteroid struck the young Moon.

A new study by scientists at the University of Arizona, USA, shows that this giant impact crater holds secrets about the formation and early evolution of the Moon.

Professor Jeffrey Andrews-Hanna and colleagues made the discovery after carefully analyzing the shape of the South Pole-Aitken basin. Giant impact basins in the solar system share a characteristic teardrop shape, tapering downwards from the impact path.

Previous assumptions suggested the asteroid hit from the south, but new analysis shows the basin actually narrows to the south, meaning the impact came from the north. This seemingly small detail has profound implications for what astronauts on the upcoming Artemis spacecraft will find when they land near the site.

Impact craters do not distribute material evenly. The lower end of the crater is often buried under a thick layer of ejecta, material ejected from deep within the Moon during the impact. The lower end of the crater receives less of this debris.

Because the Artemis spacecraft are aimed at the southern edge of the basin, the calibrated impact path means the astronauts will land exactly where they need to be to study material from deep within the Moon, essentially obtaining a core sample without having to drill.

What makes this discovery particularly interesting is that the materials in the crater contain something strange. Early in its history, the Moon was covered by a global magma ocean. As this molten layer cooled and crystallized over millions of years, heavier minerals sank to form the mantle, while lighter minerals rose to form the crust.

However, certain elements were unable to incorporate into solid rock and instead concentrated in the final residue of the liquid magma. These remnants, including potassium, rare earth elements, and phosphorus, collectively known as KREEP, failed to solidify.

The mystery remains why KREEP is concentrated almost entirely on the Earth-facing side of the Moon. This radioactive material generates heat that fuels intense volcanic activity, creating the dark basalt plains that make up the familiar “face” we see from Earth.

Meanwhile, the hidden side still has many craters and almost no volcanoes.

The new study suggests that the Moon’s crust should be significantly thicker on the far side, an asymmetry that scientists don’t yet fully understand. The team suggests that as the far side’s crust thickened, it forced the remaining magma ocean underneath toward the thinner front.

The South Pole-Aitken collision provides important evidence in support of this model. The western flank of the basin shows high concentrations of radioactive thorium, an element characteristic of KREEP-rich material, while the eastern flank does not.

This asymmetry suggests that the impact cut through the lunar crust right at the boundary where a thin, discrete layer of KREEP-rich magma still exists beneath some parts of the far side. The impact essentially opened a window into this transition zone between the KREEP-rich region of the near side and the more typical crust of the far side.

When astronauts aboard the Artemis spacecraft collect samples from this radioactive zone and bring them back to Earth, scientists will have the opportunity to examine these models in unprecedented detail.

These seemingly inanimate rocks may ultimately explain how our Moon evolved from a molten sphere into the geologically diverse world we see today, with two dramatically different hemispheres telling two very different stories of the same past.

Source: https://dantri.com.vn/khoa-hoc/ho-va-cham-lon-nhat-cua-mat-trang-co-dieu-gi-do-ky-la-dang-dien-ra-20251021231146719.htm

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh chairs meeting on railway projects](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/23/1761206277171_dsc-9703-jpg.webp)

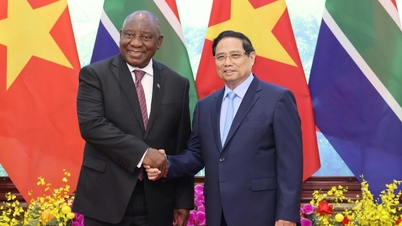

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh meets with South African President Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/23/1761226081024_dsc-9845-jpg.webp)

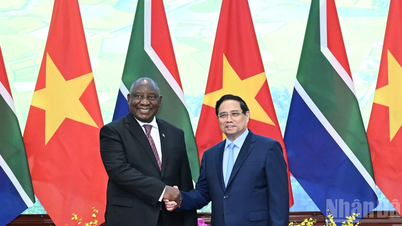

![[Photo] President Luong Cuong holds talks with South African President Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/23/1761221878741_ndo_br_1-8416-jpg.webp)

![[INFOGRAPHIC] vivo Pad5e, 12 inch 144Hz Tablet, Snapdragon 8s Gen 3 chip](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/23/1761226679125_thumb-vivo-pad5e-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)