Scott Jacqmein, a 52-year-old actor in Dallas, lives in a strange reality. His friends keep sending him promotional videos on social media that they believe are his. In them, he speaks fluent Spanish to promote a brain game, confidently introduces a horoscope app, or appears in an unfamiliar bathroom scene. But Jacqmein doesn't actually speak Spanish. He never made those videos.

His “digital twin,” an AI-generated avatar, has a commercial life of its own. The price for its existence is $750 and a trip—a one-time fee he received a year ago.

At the same time, halfway around the world, Luo Yonghao — a businessman and one of China's top livestreamers — was witnessing an economic miracle.

His digital version, powered by Baidu’s AI, conducted a live-streaming session that lasted more than six hours, raking in 55 million yuan ($7.65 million) in sales. Not only was it incredible, it far exceeded what he had ever achieved in a live-stream. “The effect of the digital character scared me,” Luo admitted.

On one side is the regret and the feeling of losing control due to the low remuneration. On the other side is the overwhelming feeling of extraordinary business performance. The story of Jacqmein and Luo is not just a contrast between East and West, but also a perfect description of the two core stages of a new economy - the digital identity economy - that is taking shape: the "raw material extraction" stage and the "refining and optimizing profits" stage.

Human identity supply chain

The digital identity economy began with a seemingly simple process: the digitization of people. Tech companies, led by ByteDance’s TikTok, created a market to “buy” raw materials – the images, voices and gestures of actors.

The business model at this stage revealed a clear power imbalance. Scott Jacqmein, a nurse turned actor who had no agent, agreed to a fee of $750. Tracy Fetter, a 55-year-old artist, received less than $1,000. Another actor accepted just $500, only to have his “doppelganger” promote sensitive products that he considered “humiliating.”

In essence, these actors are engaging in a highly risky economic transaction that is priced like a gig. They are trading an infinitely renewable asset (their image) for a one-time fee. Most importantly, these contracts contain no royalties. Whenever the avatar “Steve” (Jacqmein’s name) helps a business make a sale, all the profits go to the advertiser and the platform. Jacqmein doesn’t get a dime.

“Technology is moving faster than legal contracts,” Jacqmein warns. “And they’re luring young, unrepresented actors into the avatar trap.”

The ambiguity also extends to the scope of use. The actors believed their likeness would only appear on TikTok, but the contracts included clauses that allowed ByteDance to use their avatars on other platforms like CapCut, or by unspecified “third parties.”

The strategy is classic in supply chain building: securing inputs at minimal cost and maximum access. With estimated US advertising revenue of more than $10 billion a year, TikTok is building an advertising empire on a trove of digital assets created at almost no cost.

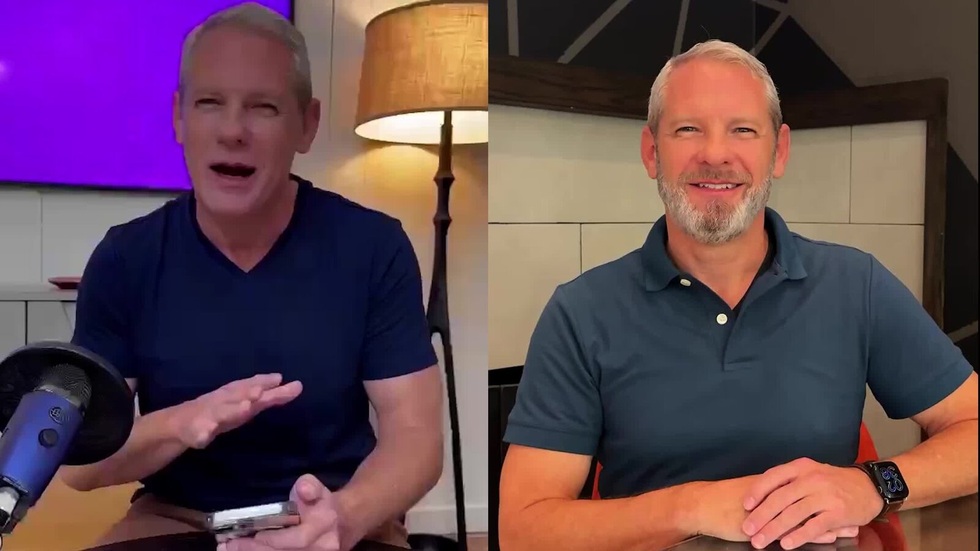

Mr. Jacqmein turned to acting after 20 years as a nurse and had no agent when he signed with TikTok (Photo: The New York Times).

Why do brands "buy" digital identities?

The need to tap into real human identities is fueled by a huge appetite from advertisers, who see AI avatars as the answer to a perennial marketing problem: how to do it faster, cheaper, and more effectively.

Optimize costs and speed: "You can A/B test with scripts, A/B test with leads, and do it all at scale at lightning speed," explains Yaniv Moore, CEO of ad tech company Tarzo.

Instead of the expensive and time-consuming traditional production process (casting, filming, post-production), a marketing director like American Eagle's Craig Brommers can create his own avatar in minutes and "program" it to say anything. This opens up the possibility of testing and optimizing ads at an unprecedented scale.

Democratizing professional advertising: For small and medium-sized businesses, this is a revolution. They don't have the budget to hire actors or professional production crews. TikTok's AI avatar, provided as a free tool, allows them to create high-quality advertising videos, increasing their competitiveness in a playing field dominated by the "big guys".

But this convenience comes with potential risks. Advertisers circumventing the law, removing the “AI Generated” label and uploading videos to other platforms like Facebook or YouTube, creating a non-transparent environment where consumers can be misled. When Jacqmein’s avatar was used to promote “male enhancement” foods, it not only violated TikTok’s terms but also directly damaged the reputation of real people.

Law professor Jeanne Fromer warns of legal gray areas: "People can have avatars express views that go against their beliefs. You have to be really willing to appear in almost any context." Brands, in the "craze" of cost optimization, can unwittingly walk into an ethical and legal minefield.

When the refined "copy" surpasses the "original"

If the US story represents the “raw mining” phase of the identity economy, Luo Yonghao’s success in China represents the “refining and optimization” phase, where the true value of digital assets is revealed.

Luo's avatar isn't a talking digital mannequin, but a high-tech creation, developed by Baidu's generative AI model. Not only does it resemble someone, it's also interactive and maintains the sales "charm" that made Luo famous.

Wu Jialu, research director at Luo's company, calls this a "DeepSeek moment" — a technological leap, similar to how DeepSeek (China's OpenAI) challenged the world .

The explosion of China’s livestreaming market has created the perfect “laboratory” for this technology. As competition has become fierce, the need to optimize performance and costs has pushed companies like Luo’s and platforms like Baidu, Alibaba, and Tencent to constantly innovate. They have been ahead of the West in transforming digital identity from a mere advertising tool into a standalone sales channel capable of generating huge revenues.

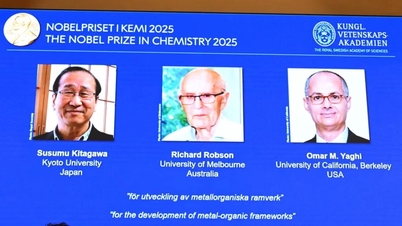

Luo Yonghao and co-host Xiao Mu used digital versions of themselves to livestream for more than 6 hours on Youxuan (Baidu), earning 55 million yuan (7.65 million USD) (Screenshot).

The future problem: Who will own the surplus value?

The journey from Scott Jacqmein’s $750 face to Luo Yonghao’s $7 million vending machine has outlined a clear value chain. Huge surplus value is being created in the middle, where AI transforms a static asset (human images) into a dynamic asset capable of generating continuous cash flow.

The core question is who deserves that share of the value?

For now, the answer is tech platforms and advertisers. “Raw material” suppliers like Jacqmein are largely removed from the profit equation. This could spark a new fight over labor rights in the digital age. Will actors’ unions negotiate new contracts that include digital royalties? Will laws catch up to protect citizens’ “digital identity rights”?

On the other hand, even those who benefit recognize the uncertainty. Yaniv Moore wonders whether companies will soon abandon using real actors to create 100% AI characters altogether to avoid legal and ethical controversies. This is a real possibility.

As technology becomes more advanced enough to create convincing “virtual” people, the need to “exploit” real people may diminish. At that point, not just actors, but models, influencers, and anyone else who makes a living off their image will face a relentless, incredibly cheap competitor.

For actors, the technology’s current shortcomings are a last consolation. Jacqmein says his avatar lacks “silver fox energy” because the technology can’t replicate his beard yet. But that “bug” will soon be fixed. As AI becomes more perfect, where will humans have the competitive edge?

The digital identity revolution is not limited to advertising or e-commerce. It touches on a deeper issue: in an increasingly digitized world, the line between our physical selves and our digital selves is blurring. The stories of Scott Jacqmein and Luo Yonghao are the first signs of a future where our identities could become assets that can be mined, valued, and traded.

Today, it’s actors. Tomorrow, it could be a call center operator’s voice being used to train AI, a journalist’s writing style being copied by a large language model, or millions of people’s health data being used to create digital health services. We are all, in some way, feeding raw data to AI machines.

The digital economy is forcing us to redefine fundamental concepts: what is labor, what is property, and how is a person’s worth measured. Scott Jacqmein’s admission that “we will never know the true consequences of this” is now not just a personal lament, but a prophecy for a generation entering a new era of great promise and great uncertainty.

Source: https://dantri.com.vn/kinh-doanh/nen-kinh-te-guong-mat-khi-ai-bien-750-usd-thanh-7-trieu-usd-20250819135332421.htm

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh attends the World Congress of the International Federation of Freight Forwarders and Transport Associations - FIATA](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/08/1759936077106_dsc-0434-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh inspects and directs the work of overcoming the consequences of floods after the storm in Thai Nguyen](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/08/1759930075451_dsc-9441-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)