Amidst the multi-colored harmony of the ethnic minorities of Tuyen Quang, there are still silences and many worries. That is the worry of the fading of identity, the disappearance of ethnic groups, the erosion of identity by bad customs, and the indifference of the youth. Lacking successors, the priceless heritage is facing many dangers... |

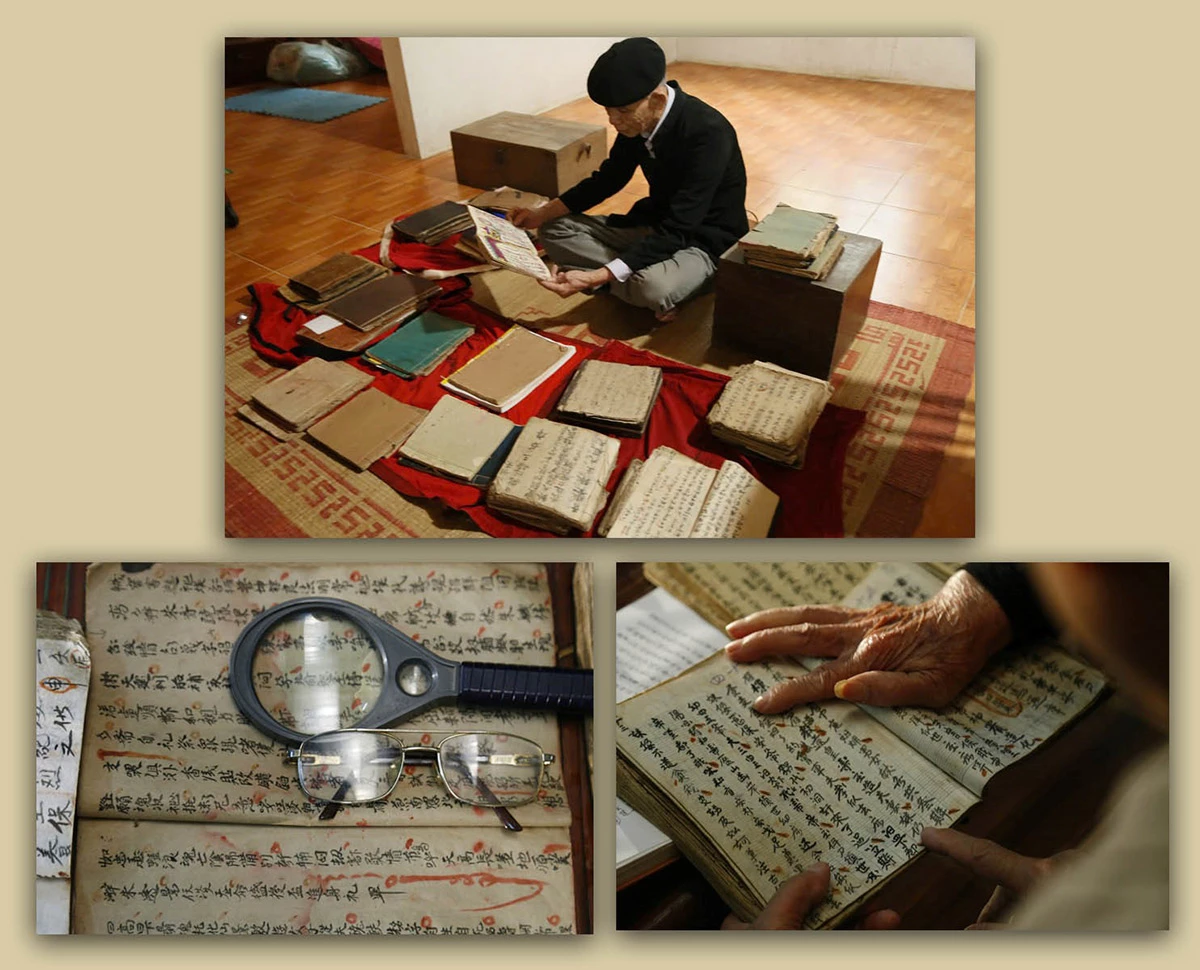

In early 2023, the sad news of the passing of folk artist Luong Long Van at the age of 95 left a big void in the Tay community in Tuyen Quang. Mr. Van is one of the very few remaining artists who are proficient and dedicated to Tay Nom script. He has tirelessly translated, compiled, and taught. He owns more than 100 ancient books and has translated and recorded dozens of books on worship rituals, prayers; advice, folk remedies...

The books published are “Van Quan Lang Tuyen Quang ”, “Some ancient Then palaces in Nom - Tay script”… In which, the 410-page book “Van Quan Lang Tuyen Quang” is a specialized document on Van Quan singing, the first village in Tuyen Quang province. The research work was awarded the Tan Trao Award in 2019.

When he was alive, folk artist Luong Long Van (left) was sought out by many students. |

The old man's small house in Yen Phu village, An Tuong ward, used to be a place for many people to come and learn, but now the teacher is missing, leaving behind endless regrets about a "living treasure" that has disappeared. Not only is it the passing of "living treasures" like Mr. Luong Long Van, but also the precious material documents are gradually disappearing.

In the past, there were many ancient books of the Dao and Tay people, often kept by shamans, prestigious people, and heads of clans. Over time, the source of ancient books and folk worship paintings is now facing the risk of being lost and seriously fading away.

Hundreds of years old books and the fear of being lost. |

- What grade are you in this year?

- Have you eaten yet?

This is a short conversation between a Dao grandfather and grandson in Hon Lau village, Yen Son commune. This situation of “grandfather asks about chicken, grandson answers about duck” is quite common between the two generations. Mr. Ly Van Thanh, Head of Hon Lau village, Yen Son commune, shared that the elderly here usually like to communicate in Dao language while the young children only understand a little, some of them cannot even speak, so the situation of “out of sync” is normal.

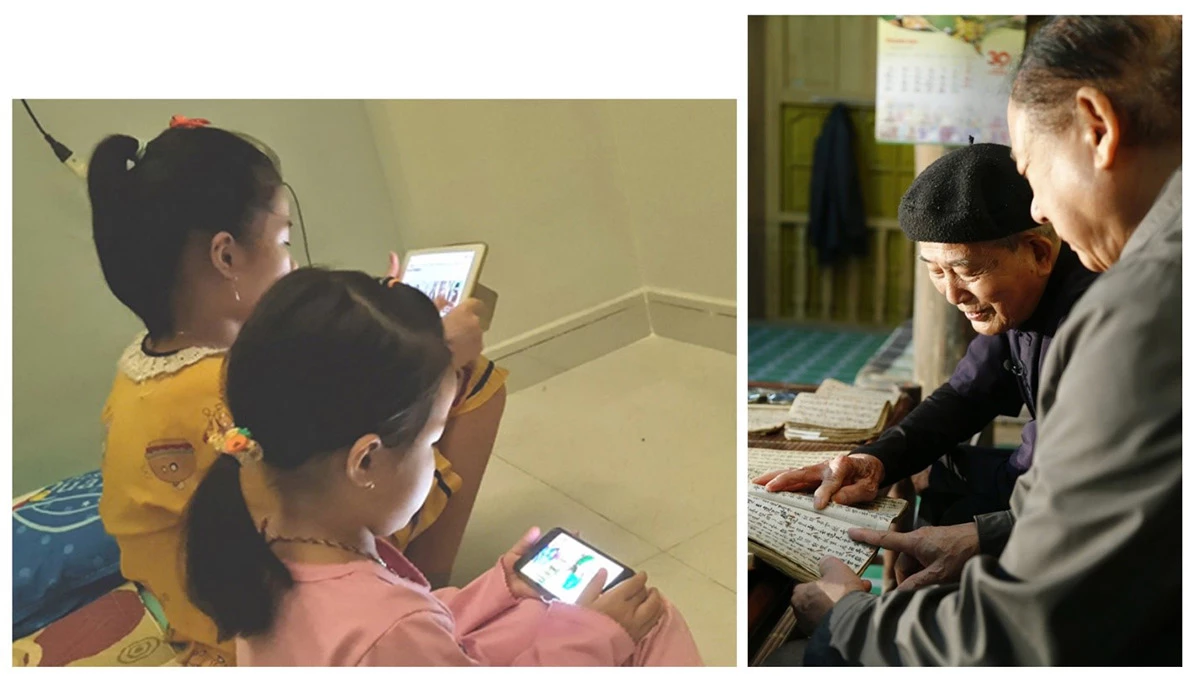

Meritorious Artisan Ma Van Duc commented that, in the current trend of integration and development, many families of Tay, Dao, Nung, Cao Lan, Mong… young people only know how to speak the common language. Some even know but are afraid to communicate, so the ethnic language is gradually fading away.

Meritorious artist Ma Van Duc actively teaches Then to the younger generation |

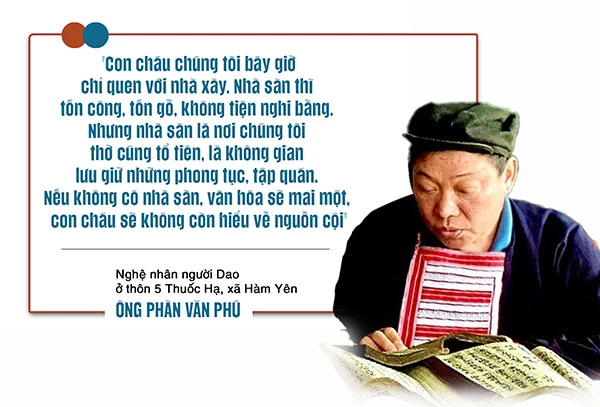

For the Dao people – an ethnic group with its own writing system – the decline is even more urgent. Artisan Trieu Chan Loang in Tan Quang commune quietly preserves ancient books, prayers, and ceremonies of coming of age. But the younger generation is gradually becoming indifferent, considering them impractical. “If no one takes over the profession, who will read the prayer books and perform the ancestral ceremonies in the future?” - Mr. Loang sighed, as if speaking for countless artisans who are quietly facing the risk of having no successors for their culture.

Such indifference is not without reason. Mrs. Ha Thi Xuyen, Dong Huong village, Chiem Hoa commune confided: “Young people now like to surf TikTok and Facebook. They wear jeans and T-shirts instead of traditional costumes, speak Kinh instead of ethnic languages, and sing dance songs from CDs instead of their own folk songs.” The sighs of artisans and village elders are an urgent warning about a future where national identity may only be a memory.

Costumes are an essential part of culture. Younger generations and general audiences may confuse the performance version with the original, thereby blurring accurate cultural knowledge. |

Not only language, traditional costumes are also being replaced by convenience and simplicity. If in the past, ethnic minorities such as Tay, Nung, Mong still proudly wore costumes with strong national cultural identity in their daily activities, now, especially men and young people, rarely wear national costumes. Visual heritage that once had a strong community imprint is gradually relegated to festivals, even being modernized, commercialized, losing its inherent standards.

Wearing traditional costumes from childhood is a way to nurture love and awareness of preserving national identity. |

The story of a group of young people Hoang Ngoc Hoan, Ninh Thi Ha and Nguyen Van Tien in Doan Ket village, Nhu Han commune is a living proof. With their love for Cao Lan culture, they together built the TikTok channel "Ban San chay".

In just under a year, the channel has attracted 75 thousand followers, many videos have reached millions of views, vividly introducing the culture, customs, writing, and language of the Cao Lan people. The project promises to spread the culture of their ethnic group more. However, after less than a year, Ninh Thi Ha had to leave the group to work as a worker at a company in Hanoi.

The burden of making a living forced the young girl to temporarily put aside her passion to find a more stable source of income, leaving a void and regret for her passionate project.

Tiktoker Hoang Ngoc Hoan created the video. |

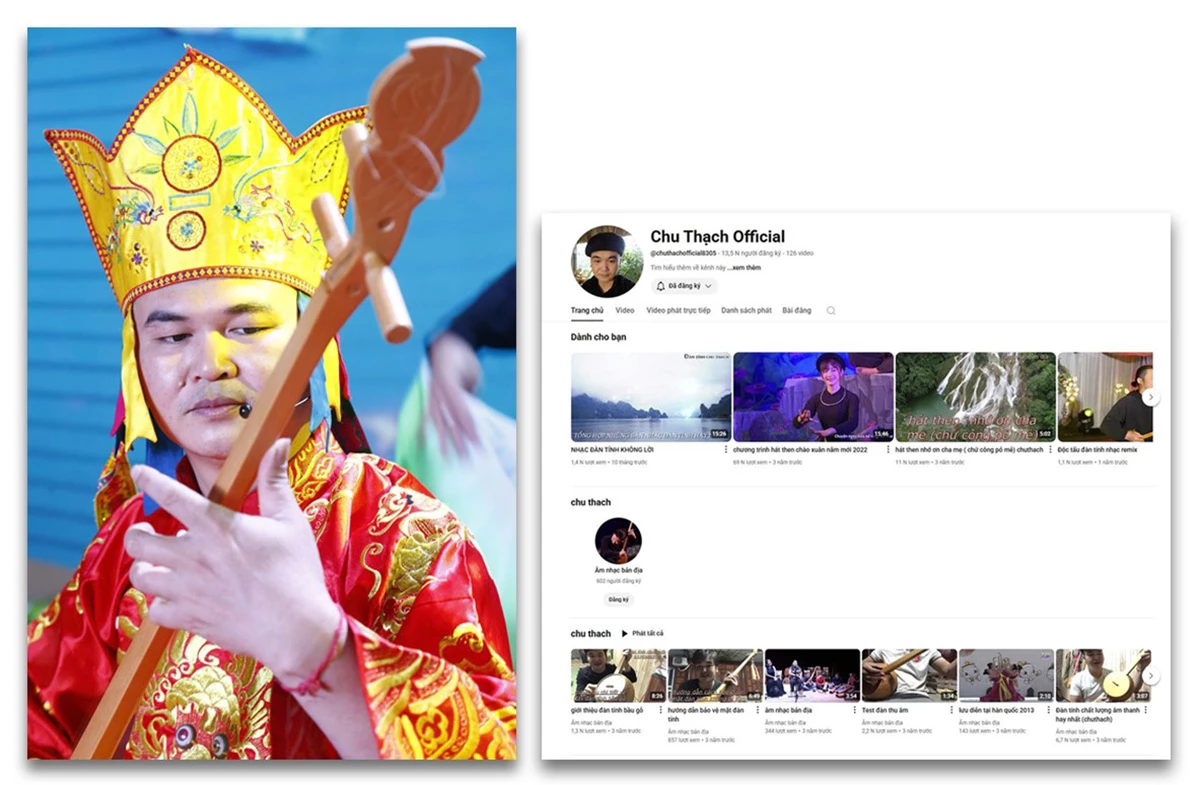

Similarly, the journey of young artist Chu Van Thach is a story of extraordinary talent and effort. He has gradually brought the 12-string Tinh instrument to the big stage, receiving praise at the 2nd National Congress of Ethnic Minorities in Vietnam in 2020. Most recently, Chu Van Thach also won the Silver Prize at the National Instrument Solo Festival held in Hanoi .

Not only performing, Mr. Thach also actively teaches Then singing and Tinh lute through two YouTube channels “Dan tinh Chu Thach” (teaching Tinh lute from basic to advanced) and “Chu Thach Official” (posting performances). He also teaches directly, even using Facebook and Zoom to teach online to Then singing and Tinh lute lovers who live far away.

Artisan Chu Thach is passionate about spreading Tay culture. |

However, despite his talent and enthusiasm, Chu Van Thach, like many other young people, still faces the pressure of making a living. He has to do many other jobs, from mechanics to assembling agricultural machinery, to ensure his life. There are times, he shares, when the time for his passion is significantly reduced because of the hustle and bustle of work.

The stories of Ninh Thi Ha and Chu Van Thach are not only their own but also represent many other young artisans who are day and night preserving and promoting the national cultural identity. They have knowledge, enthusiasm, and the ability to adapt to modern technology to bring the heritage far and wide. However, without support mechanisms and policies to create favorable conditions for them to make a living from their profession and passion, the burden of making a living will always be a big obstacle.

Amidst the modern pace of life, in the villages of Tuyen, the increasing appearance of solidly built houses with modern tiled roofs is gradually pushing away traditional architectural spaces. This change is not simply a matter of housing, but also a concern about an increasingly large cultural gap in community life.

Along the roads winding into the villages in Tuyen Quang, the image of sturdy wooden stilt houses gradually becomes a memory. Mr. Ma Van Vinh, Dong Huong village, Chiem Hoa commune, could not help but feel nostalgic when recalling: "In the past, going from Chiem Hoa, Kien Dai, Minh Quang to Thuong Lam, everywhere you could see stilt houses hidden in the morning mist, vaguely behind the palm hills. That scene was peaceful and beautiful. Now there are only a few houses, perhaps about to be demolished. The flickering stoves have also been replaced by gas stoves and electric stoves." Mr. Vinh's words are not only the nostalgia of an individual, but also the concern of an entire generation.

Modern houses are gradually replacing traditional stilt houses in many Tay villages in Tuyen Quang. |

Traditional cultural spaces are also gradually shrinking and disappearing along with the stilt houses of the Tay people and the rammed earth houses of the Mong people. Mrs. Nguyen Thi Cam (95 years old) in Ngoi Ne, Na Hang commune remembers her youth full of laughter: "The stilt houses in the past were very large, both as a place for living and activities of the family and as a place for cultural activities of the whole community.

The rooms were symbolically separated by black indigo curtains, not tulle curtains like today. The blankets and pillows were all brocade products woven by the locals. Now, the houses are modern, so the space for cultural activities is no longer there; the brocade blankets are gradually being replaced.

Tuyen Quang folk culture researcher Nguyen Phi Khanh also commented: "The gradual disappearance of traditional stilt houses and rammed earth houses is not only the loss of a type of architecture but also the loss of a space for community cultural activities. This leads to a breakdown in the teaching and practice of rituals and folk songs.

Therefore, there needs to be policies and mechanisms to support and encourage people to preserve traditional houses, while incorporating convenient elements to suit modern life."

In the life of the Mong community, the custom of "wife pulling" is a unique cultural feature, which expresses the sincere feelings of couples and exalts the qualities of women. However, when the original values are not fully preserved, this custom can easily turn into illegal behavior.

A clear example of this is the incident that occurred in 2022 in Pa Vi Ha village, Meo Vac commune. GMC, born in 2006, took advantage of the "wife-pulling" custom to force a young girl to become his wife. Despite the victim's cries and pleas, C. still tried to drag her away, despite her protests. Only when the commune police force arrived was the illegal act stopped. This incident is not only a wake-up call about ethics but also raises legal questions about how to protect human rights within the framework of customs.

“Wife pulling” is a unique marriage proposal ritual of the Mong people. It needs to be understood and practiced correctly to avoid turning into an illegal act. |

Not only the Mong, for the Dao, the Cap Sac ceremony also reveals consequences when misunderstood. Mr. Trieu Duc Thanh (Ha Giang 2 ward) worries: "The Cap Sac ceremony marks the turning point of maturity of a son in the community, qualified to worship ancestors, participate in village and family affairs. But that does not mean maturity in physical, mental or legal aspects. Unfortunately, there are places where there is a misunderstanding about maturity in the Cap Sac ceremony, leading to early marriage, dropping out of school, affecting the future of an entire generation."

The heartbreaking reality is the story of a boy named D.VB, from Lung Tao village, Cao Bo commune. At the age of 10, D.VB had his Cap sac ceremony, and at the age of 14, he "settled down" with a girl from the same village. By the age of 18, D.VB was already the father of two young children. That young marriage quickly fell apart. Lung Tao village chief Dang Van Quang said: "D.VB's family is one of the poor households in the commune. Unstable work makes the single father's livelihood burden even heavier."

In Nam An village, Tan Quang commune - where 100% of the population is Dao, traditional rituals are still maintained but also contain many "deeply rooted" bad customs. Artisan Trieu Chan Loang said: The Cap sac ceremony lasts 3 days and 3 nights, slaughtering up to 5 pigs (80-100kg/pig), not to mention poultry, wine, rice, wages for 5 shamans... The total cost is about 50 million VND, or even more. For poor families who cannot organize the Cap sac ceremony, their sons will be considered "children" for life in the community.

The economic burden still lingers in the Dao people's wedding ceremony with a heavy dowry: 55 old silver coins (about 55 million VND), 100 kg of rice, 100 kg of wine, 100 kg of meat. The wedding lasts 3 days and 3 nights with the slaughter of many livestock. Mr. Loang sadly said: "Without money, you cannot get married, many people have to live with the wife's family. Many couples have to postpone their wedding or fall into debt after the wedding."

On the Dong Van Stone Plateau, many Mong funerals have become bad customs, leaving many consequences in modern life. In 2024, Mr. VMCh's family, village 1, Meo Vac commune, still held their mother's funeral according to tradition: lasting for many days, slaughtering nearly 10 cows and many pigs, placing the body on a wooden stretcher in the middle of the house, not embalming immediately, performing a "rice feeding" ceremony and other spiritual rituals that pollute the environment. Despite economic difficulties, Mr. Ch. still shouldered large funeral expenses to pay off the "debt", causing the family to fall into poverty.

Not putting the dead in coffins and exposing the bodies is a painful problem for the Mong people in the Dong Van Stone Plateau. |

The above stories show that, although containing profound cultural values, traditional customs still need to be re-examined, selected and adjusted to suit modern life so as not to become barriers for the future.

In Tuyen Quang, there is a sad reality: the gradual disappearance of the two ethnic groups, the Tong and Thuy – small communities but possessing unique cultural treasures. With a population of less than 100 people each, they are facing the risk of "disappearing" from the cultural map of Vietnam.

Song ethnic family. |

In Dong Moc village, Trung Son commune, where the Tong ethnic group lives, Mr. Thach Van Tuc - a prestigious person in the community - could not hide his sadness when sharing: "We have our own costumes, customs, and language. However, over time, they have gradually faded away. Currently, according to the citizen identification card, all documents state that we are the Pa Then ethnic group."

|

The Thuy ethnic group in Tuyen Quang has made cultural researchers even more concerned. Thuong Minh village, Hong Quang commune, hidden in a valley with towering rocky mountains, is the only place on this S-shaped strip of land where the Thuy people live. With 21 households and nearly 100 people, the Thuy ethnic group currently has three main clans: Ly, Mung and Ban.

Comrade Chau Thi Khuyen, Chairman of the People's Committee of Minh Quang commune, shared: "In the province, there is a Thuy ethnic group living, but it is not listed, not recognized, and legally outside the system, so it affects the rights of the people. Therefore, the government has mobilized the Thuy community to join the Pa Then ethnic group, to ensure the rights of the people."

Although the Thuy ethnic group merged with the Pa Then ethnic group to ensure their civil rights, for the elderly, Mr. Mung Van Khao, 81 years old, it is the pain of losing their roots: "Now, the identity card of each Thuy person has the name of the Pa Then ethnic group. Future generations will no longer know that they belong to the Thuy ethnic group. The language of the Thuy ethnic group is now only known to old people like me, and the whole village has only 3 sets of costumes. This is an inconsolable sadness."

The Thuy ethnic group in Thuong Minh currently only preserves 3 sets of traditional clothing. |

The "disappearance" of an ethnic group is not only the loss of a community, but also the loss of a valuable part of the country's cultural heritage. Therefore, there is a need for more comprehensive and timely policies to preserve and promote the cultural values of ethnic minorities, especially those that are facing the risk of extinction.

Performed by: Hoang Bach - Hoang Anh - Giang Lam - Bien Luan

Thu Phuong - Bich Ngoc

Part 1: Opening the treasure trove of Tuyen Quang ethnic groups

Part 2: Passing on the legacy

Source: https://baotuyenquang.com.vn/van-hoa/202508/ky-3-khoang-lang-sau-ban-hoa-am-ruc-ro-e7f10b1/

![[Photo] The 1st Congress of Phu Tho Provincial Party Committee, term 2025-2030](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/30/1507da06216649bba8a1ce6251816820)

![[Photo] Solemn opening of the 12th Military Party Congress for the 2025-2030 term](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/30/2cd383b3130d41a1a4b5ace0d5eb989d)

![[Photo] President Luong Cuong receives President of the Cuban National Assembly Esteban Lazo Hernandez](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/30/4d38932911c24f6ea1936252bd5427fa)

![[Photo] Panorama of the cable-stayed bridge, the final bottleneck of the Ben Luc-Long Thanh expressway](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/30/391fdf21025541d6b2f092e49a17243f)

Comment (0)