|

| Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai and comrade Le Duc Tho in Beijing. |

From the Geneva Conference

On May 8, 1954, exactly one day after the resounding victory of Dien Bien Phu, the Conference on Indochina opened in Geneva with the participation of nine delegations: the Soviet Union, the United States, Great Britain, France and China, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, the State of Vietnam, the Kingdom of Laos and the Kingdom of Cambodia. Vietnam repeatedly requested to invite representatives of the Lao and Cambodian resistance forces to attend the Conference but was not accepted.

Regarding the context and intentions of the parties participating in the Conference, it can be emphasized that the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States had developed to its peak. Along with the Cold War was a hot war in the Korean Peninsula and Indochina; a trend of international détente emerged. On July 27, 1953, the Korean War ended, and Korea was divided at the 38th parallel as before.

In the Soviet Union, after J. Stalin passed away (March 1953), the new leadership headed by Khrushchev adjusted its foreign policy strategy: promoting international détente to focus on internal issues. Regarding China, which suffered losses after the Korean War, this country made its first five-year plan for socio -economic development, wanting to end the Indochina War; needed security in the South, broke the siege and embargo imposed by the United States, pushed the United States away from the Asian continent and promoted the role of a major power in solving international issues, first of all, Asian issues...

After eight years of war, France, which had lost lives and resources, wanted to get out of the war with honor and still maintain its interests in Indochina. On the other hand, internally, the anti-war forces, demanding negotiations with the Ho Chi Minh Government, increased pressure. Britain did not want the Indochina war to spread, affecting the consolidation of the Commonwealth in Asia and supporting France.

Only the United States, not wanting any negotiations, tried to help France to intensify the war and increase its intervention. On the other hand, the United States wanted to attract France to join the Western European defense system against the Soviet Union, so it supported France and Britain to participate in the Conference.

In the above context, the Soviet Union proposed a Quadrilateral Conference consisting of the foreign ministers of the Soviet Union, the United States, Great Britain and France in Berlin (from January 25 to February 18, 1954) to discuss the German issue, but failed, so it switched to discussing the Korean and Indochina issues. Because of the Korean and Indochina issues, the Conference unanimously agreed to invite China to participate as proposed by the Soviet Union.

For Vietnam, on November 26, 1953, when answering reporter Svante Lofgren of Expressen newspaper (Sweden), President Ho Chi Minh expressed his readiness to participate in negotiations on a ceasefire.

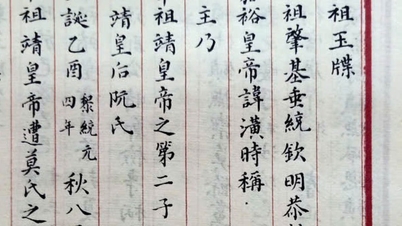

After 75 days of arduous negotiations with 8 general meetings and 23 small meetings along with intensive diplomatic contacts, the Agreement was signed on July 21, 1954, including three ceasefire agreements in Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia and the Final Declaration of the Conference with 13 points. The US delegation refused to sign.

The main content of the Agreement is that the countries participating in the Conference declare to respect the independence, sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity of Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia; cease hostilities, ban the import of weapons, military personnel, and the establishment of foreign military bases; conduct free general elections; France withdraws troops to end the colonial regime; the 17th parallel is a temporary military demarcation line in Vietnam; Laotian resistance forces have two assembly areas in Northern Laos; Cambodian resistance forces demobilize on the spot; the International Supervision and Control Commission includes India, Poland, Canada...

Compared to the Preliminary Agreement of March 6 and the Provisional Agreement of September 14, 1946, the Geneva Agreement was a great step forward and an important victory. France had to acknowledge independence, sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity and withdraw its troops from Vietnam. Half of our country was liberated, becoming a great rear base for the struggle for complete liberation and national unification later.

The agreement is of great significance, however, it also has some limitations. The agreement leaves valuable lessons for Vietnamese diplomacy such as independence, self-reliance and international solidarity; combining military, political and diplomatic strength; strategic research... and especially strategic autonomy.

In an answer to Expressen newspaper on November 26, 1953, President Ho Chi Minh affirmed: “… The ceasefire negotiations are mainly a matter between the Government of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV) and the French Government”. However, Vietnam participated in multilateral negotiations and was only one of nine parties, so it was difficult to protect its own interests. As Senior Lieutenant General and Professor Hoang Minh Thao commented: Unfortunately, we were negotiating at a multilateral forum dominated by major countries, and the Soviet Union and China also had calculations that we did not fully understand, so Vietnam's victory was not fully exploited.

|

| General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Brezhnev received and held talks with comrade Le Duc Tho after he initialed the Paris Agreement on his way back home, January 1973. |

To the Paris Conference on Vietnam

In the early 1960s, the international situation had important developments. The Soviet Union and the Eastern European socialist countries continued to consolidate and develop, but the Sino-Soviet conflict became increasingly fierce, and the division within the international communist and workers' movements deepened.

The national independence movement continued to grow strongly in Asia and Africa. After the failure at the Bay of Pigs (1961), the US abandoned the strategy of “massive retaliation” and proposed a strategy of “flexible response” aimed at the national liberation movement.

Applying the "flexible response" strategy in South Vietnam, the US conducted a "special war" to build a strong Saigon army with American advisors, equipment and weapons.

The “special war” was in danger of going bankrupt, so in early 1965, the US sent troops to Da Nang and Chu Lai, starting a “local war” in South Vietnam. At the same time, on August 5, 1964, the US also began a war of destruction in the North. The 11th Central Conference (March 1965) and 12th (December 1965) affirmed the determination and direction of resistance against the US to save the country.

After the successful counter-offensive in the two dry seasons of 1965-1966 and 1966-1967, against the war of destruction in the North, our Party decided to switch to the strategy of "fighting while negotiating". In early 1968, we launched a general offensive and uprising, which, although unsuccessful, dealt a fatal blow, shaking the will of the US imperialists to invade.

On March 31, 1968, President Johnson was forced to decide to stop bombing North Vietnam, ready to send representatives to dialogue with the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, opening the Paris negotiations (from May 13, 1968 - January 27, 1973). This was an extremely difficult diplomatic negotiation, the longest in the history of Vietnamese diplomacy.

The conference took place in two phases. The first phase from May 13 to October 31, 1968: Negotiations between the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and the United States on the US completely ending the bombing of North Vietnam.

The second phase from January 25, 1969 to January 27, 1973: The 4-party conference on ending the war and restoring peace in Vietnam. In addition to the DRV and the US delegations, the conference had the participation of the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (NLF)/Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam (PRG) and the Saigon government.

From mid-July 1972, Vietnam proactively moved to substantive negotiations to sign the Agreement after winning the Spring-Summer 1972 campaign and the US presidential election was approaching.

On January 27, 1973, the parties signed a document called the Agreement on Ending the War and Restoring Peace in Vietnam with 9 chapters and 23 articles, along with 4 protocols and 8 understandings, meeting the four requirements of the Politburo, especially the withdrawal of US troops and the stay of our troops.

The Paris negotiations left many great lessons for Vietnamese diplomacy: independence, self-reliance and international solidarity; combining national and contemporary strength; diplomacy as a front; the art of negotiation; public opinion struggle; strategic research, especially independence, self-reliance.

Drawing lessons from the Geneva Conference in 1954, Vietnam independently planned and implemented its resistance policy against the US, as well as its foreign policy and diplomatic strategy of independence and autonomy, but always in coordination with fraternal countries. Vietnam directly negotiated with the US... This was the most fundamental reason for the diplomatic victory in the resistance war against the US to save the country. These lessons still hold true.

|

| Cover of the New York Daily News on January 28, 1973 with the content: Peace signed, end of draft: Vietnam War ends. |

Strategic autonomy

Is the lesson of independence and autonomy in the Paris negotiations (1968-1973) related to the issue of strategic autonomy that international scholars are debating today?

According to the Oxford dictionary, “strategy” involves identifying long-term goals or interests and the tools to achieve those goals; while “autonomy” reflects the ability to self-govern, independence, and not be influenced by external factors. “Strategic autonomy” refers to the independence and self-reliance of a subject in determining and implementing its important, long-term goals and interests. Many scholars have generalized and given different definitions of strategic autonomy.

In fact, the idea of strategic autonomy was affirmed by Ho Chi Minh long ago: “Independence means we control all our work, without outside interference”. In the Appeal on Independence Day, September 2, 1948, he expanded the concept: “Independence without having a separate army, separate diplomacy, separate economy. The Vietnamese people absolutely do not crave that kind of fake unity and independence”.

Thus, not only is the Vietnamese nation independent, self-reliant, unified and territorially intact, but the nation’s diplomacy and foreign affairs must also be independent and not be dominated by any power or force. In the relationship between international Communist and workers’ parties, he affirmed: “Parties, whether large or small, are independent and equal, and at the same time united and unanimous in helping each other.”

He also clarified the relationship between international aid and self-reliance: “Our friendly countries, first of all the Soviet Union and China, tried their best to help us selflessly and generously, so that we could have more conditions to be self-reliant.” To strengthen solidarity and international cooperation, we must first promote independence and autonomy: “A nation that is not self-reliant but waits for help from other nations does not deserve independence.”

Independence and self-reliance are prominent and consistent thoughts in Ho Chi Minh's thought. The fundamental principle of that thought is "if you want others to help you, you must first help yourself". Maintaining independence and self-reliance is both a guideline and an immutable principle of Ho Chi Minh's thought.

Learning from the Geneva negotiations, Vietnam has highlighted the lesson of independence and self-reliance in negotiating the Paris Agreement, which is Ho Chi Minh's fundamental foreign policy ideology. That is also the strategic autonomy that international researchers are currently discussing enthusiastically.

1. Senior Lieutenant General, Professor Hoang Minh Thao “Dien Bien Phu Victory with the Geneva Conference”, book Geneva Agreement 50 Years in Review, National Political Publishing House, Hanoi, 2008, p. 43.

Source: https://baoquocte.vn/tu-geneva-den-paris-ve-van-de-tu-chu-chien-luoc-hien-nay-213756.html

![[Photo] Hanoi morning of October 1: Prolonged flooding, people wade to work](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/1/189be28938e3493fa26b2938efa2059e)

![[Photo] President visits Vietnam's Permanent Mission to the United Nations](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/24/b97c02dea2634eb38b94b1d6145671e3)

![[Photo] Panorama of the cable-stayed bridge, the final bottleneck of the Ben Luc-Long Thanh expressway](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/30/391fdf21025541d6b2f092e49a17243f)

Comment (0)