China is facing a new set of challenges from more severe, extreme and violent weather events.

At 3:44 a.m. on June 19, Tang Kaili, a home appliance store owner in Guilin City, southern China, was still sleeping soundly when a text message from the city government appeared on his phone screen. The message warned that a reservoir upstream would start releasing floodwaters at 5 a.m. and asked residents to evacuate. Tang did not pay attention and fell asleep.

For a week, it has been pouring rain in Guilin – a tourist city in the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, famous for its tranquil lakes, winding rivers and rich cave systems. Some reservoirs have been forced to release floodwaters because they can no longer contain the large amount of water falling from the torrential rains. However, few could have expected that the latest flood release would be the last straw, causing the most serious flooding in Guilin in nearly 30 decades.

At 8:50 a.m., Tang received a call from the manager of her residential complex, informing her that the water level was rising rapidly. Tang rushed outside and found that the water was knee-deep. She decided to wade through the streets to get to the store to get her belongings. When she arrived, her store was already submerged in water.

“The manager told me I had to evacuate immediately because the water rose too fast. When I came back the next day, my beautiful shop had turned into a pile of mud. I invested 1 million yuan (about 138,000 USD) in the shop and now I lost everything. It all happened so suddenly,” Tang said sadly.

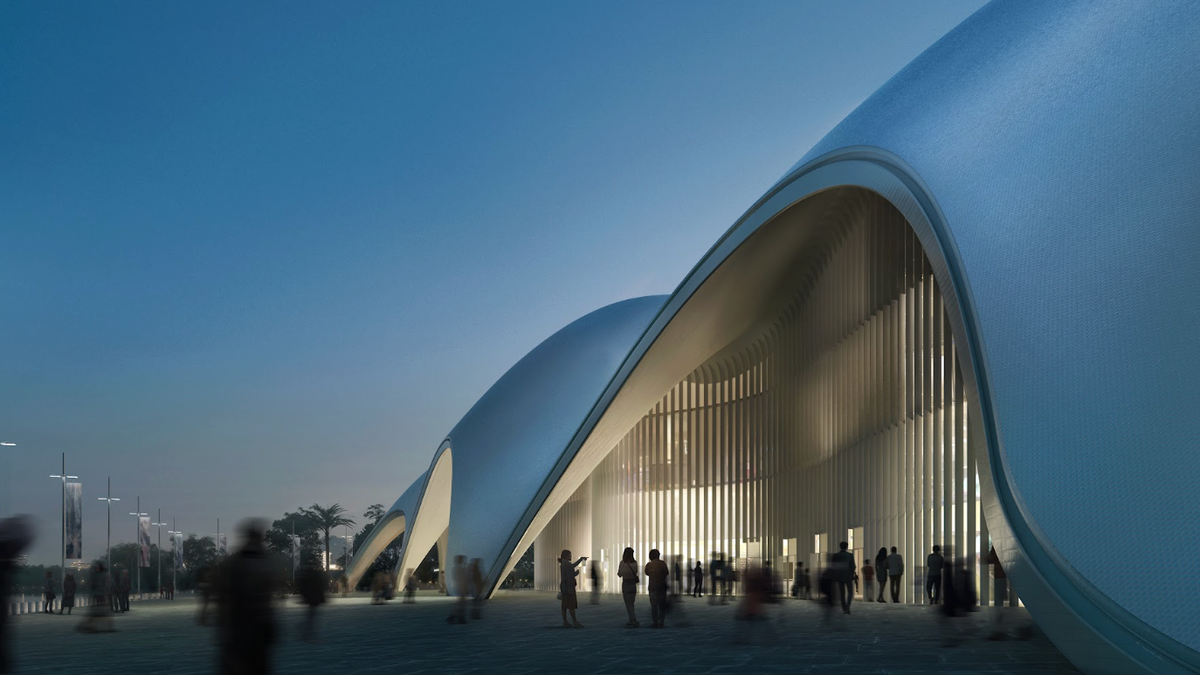

|

| China is facing a new set of challenges in the face of more severe, extreme and violent weather events. (Source: SCMP) |

Floods and droughts are raging

Guilin is not the only city to suffer from the harsh weather conditions this summer. A large area of China – 12 provinces stretching from the south to the northeast – has been severely inundated by heavy rain and floods. Meanwhile, four other provinces – Hebei in the north, central Shanxi and Henan , and eastern Shandong – have been scorched by drought.

China has just experienced its hottest July and the hottest month since 1961, with the western Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, the eastern city of Hangzhou and the southern cities of Fuzhou and Nanchang regularly experiencing more than 20 days of sweltering weather with temperatures above 35 degrees Celsius, according to the National Climate Center.

The government has yet to release a death toll from the severe weather, but 30 people have died and 35 others are reported missing since Typhoon Gaemi made landfall in central China's Hunan province in late July. Before Typhoon Gaemi, more than 20 floods had struck the country since April, causing casualties and damage from Guangdong in the south, Chongqing in the southwest, all the way to Hunan.

Extreme weather has affected the lives of hundreds of millions of people and caused billions of yuan in damage.

China also saw its early-season rice harvest fall due to flooding in the country's rice granaries Jiangxi and Hunan, adding pressure on annual output, especially at a time when Beijing is pushing to boost food security.

New series of challenges

Despite its extensive experience in responding to natural disasters – from issuing warnings and implementing preventive measures, to mobilizing the military, law enforcement, medical staff and volunteers for rescue and relief – the Northeast Asian country is facing a new set of challenges in the face of more sudden and intense extreme weather events.

“Since the beginning of the 21st century, extreme heat days in China have increased significantly, as have heavy rainfall events. China is particularly vulnerable to extreme weather caused by climate change,” the China Meteorological Administration (CMA) said in a report released on July 4.

China's average annual temperature in 2023 is expected to reach its highest level since records began in 1901. Extreme weather events are increasing rapidly. Average sea levels are rising faster in coastal areas and glaciers in western regions are melting at a rapid pace, the report said.

Ronald Li Kwan-kit, from the Chinese University of Hong Kong and a member of the Hong Kong Meteorological Society, said the main cause was rising greenhouse gas emissions.

“Southern China usually experiences heavy rainfall in the summer as part of the… monsoon season. But the intensity of the rainfall may be affected by climate change, so it may become more severe,” the expert analyzed.

Extreme weather is also having a profound impact on China’s economic activities. Typhoons are causing serious damage to the shipping industry, while more frequent and intense floods and droughts are damaging China’s agriculture, according to Ronald Li Kwan-kit. And the most urgent solution is to reduce carbon emissions.

China is the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases. In April 2021, President Xi Jinping said the country would “strictly control” coal-fired power generation projects, peaking in 2025 and beginning a phase-out in 2026, as part of a national target to achieve net-zero emissions by 2060.

But those targets are in danger of being derailed as the number of new coal-fired power plants approved quadrupled between 2022 and 2023, compared with the five years from 2016 to 2020, according to the Center for Energy and Clean Air. The surge comes as China pushes to recover from the pandemic.

“Given China’s central role in global production chains, what happens in China is clearly not just limited to the domestic sphere – the shocks will ripple globally,” said Sourabh Gupta, senior policy fellow at the Institute for China-America Studies in Washington. The long-term solution, Gupta said, is for China to move up the domestic value chain.

According to this expert, Beijing needs to cut carbon emissions in production and exports, improve green energy production capacity, save costs and related services.

The key is in technology

China's flood control law should set higher standards for flood-prevention facilities and expand the application of technology in severe weather forecasting, advance warning and digital management of barriers, dams and flood-retention areas, said Ma Jun, director of the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs, a Beijing-based NGO.

The last revision of the Law took effect in 2016. In early July, China's Ministry of Water Resources held a workshop to solicit expert opinions on further revisions to the Law to “address new and old problems” in disaster prevention.

Last year, China built at least two weather forecast models that used powerful technology to predict severe weather conditions such as tropical storms and heavy rains much more accurately than traditional forecasting models.

Faith Chan, Associate Professor of Environmental Sciences at the University of Nottingham in Ningbo, said China has made positive progress in improving disaster preparedness and response, but ultimate success still depends on government policy.

However, the expert also warned that while a unified data system could allow for “more organized and effective practices” to address natural disasters, thereby minimizing casualties and economic losses, “a lack of flexibility and rigidity in handling disasters caused by extreme weather could affect the effectiveness of operations.”

According to this expert, the need to apply technology is increasingly urgent. “The key is still the decision and action from the government, allowing the use of technologies such as big data or artificial intelligence,” he said.

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh chaired a meeting of the Steering Committee on the arrangement of public service units under ministries, branches and localities.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/06/1759767137532_dsc-8743-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh chairs a meeting of the Government Standing Committee to remove obstacles for projects.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/06/1759768638313_dsc-9023-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)