In the Barents Sea, a rare and dramatic event has taken place: Millions of Arctic herring have gathered to spawn, forming a giant school. However, this dense concentration has attracted the attention of their top predators: Atlantic cod.

In a lightning attack, millions of herring were devoured, turning the area into a bloody feast. It was the first time scientists had been able to observe and record a predation event on such a large scale.

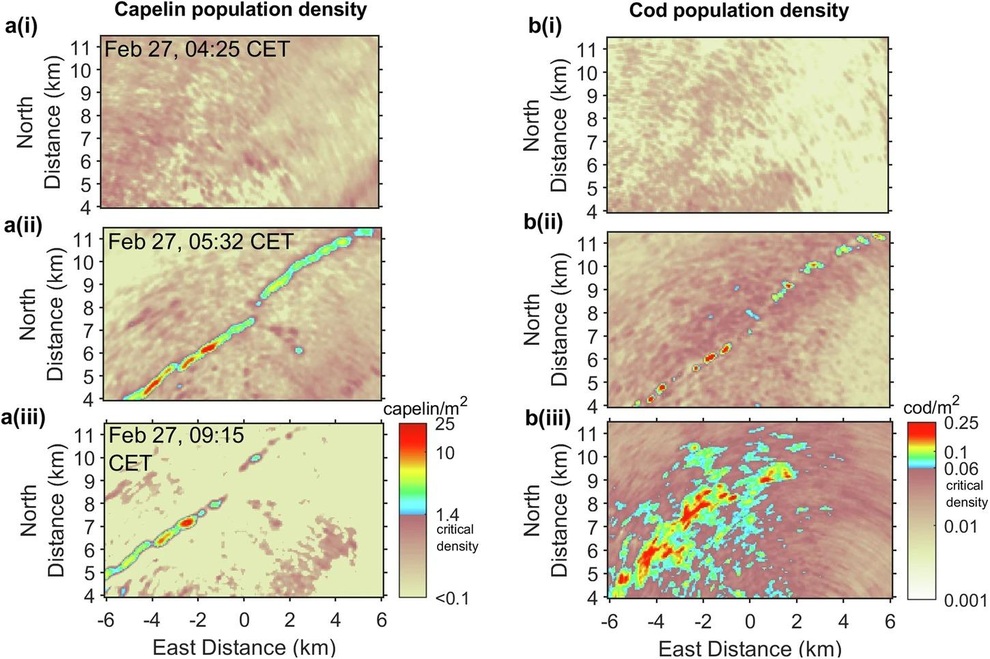

Researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Norway used an advanced acoustic imaging technology called the Ocean Acoustic Waveguide Remote Sensing System (OAWRS) to record the entire event.

The technology allows scientists to detect fish movements over a large area. Professor Nicholas Makris, lead author of the study, explained that they used the resonance properties of the swim bladders in fish to differentiate species: the deep call of cod and the high-pitched call of herring.

As the sun rose on February 27, 2024, the herring, which had been scattered across the coast, began to congregate in dense schools. This strategy helped them protect each other, but also made them an attractive target. Immediately, a huge school of cod launched a coordinated attack.

In just a few hours, some 2.5 million cod had consumed more than 10 million herring, nearly half the school. “It was a tight battle for survival,” Makris said, underscoring the brutality of nature’s laws.

While this event did not have a major impact on the overall herring population, it has important implications for marine ecology. Herring is a key link in the food chain, playing a vital role in maintaining Atlantic cod populations.

However, climate change is melting Arctic sea ice, forcing herring to migrate further to reach their spawning grounds. This makes them more vulnerable to large-scale predation.

This study is a warning about the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

“In our study, we found that natural catastrophic predation events can alter the local predator-prey balance in just a few hours,” Makris notes.

If climate and human pressures reduce these ecological hotspots, such events could have serious consequences for dependent species."

Hoping to better understand these complex interactions, Makris and his colleagues plan to continue deploying the OAWRS technology. The goal is to monitor the behavior of other fish and predict potential threats before it’s too late.

“When a population is on the brink of collapse, you often see a last shoal of fish,” Makris notes. “And when that last large, dense shoal is gone, collapse occurs.”

These findings were reported in the journal Communications Biology.

Source: https://dantri.com.vn/khoa-hoc/dieu-gi-khien-hon-10-trieu-con-ca-tren-bien-barents-mat-tich-sau-vai-gio-20250927051522689.htm

![[Photo] High-ranking delegation of the Russian State Duma visits President Ho Chi Minh's Mausoleum](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/28/c6dfd505d79b460a93752e48882e8f7e)

![[Photo] Joy on the new Phong Chau bridge](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/28/b00322b29c8043fbb8b6844fdd6c78ea)

![[Photo] The 4th meeting of the Inter-Parliamentary Cooperation Committee between the National Assembly of Vietnam and the State Duma of Russia](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/28/9f9e84a38675449aa9c08b391e153183)

Comment (0)