Alarming reality

This means that most people on the continent are breathing poor quality air and suffering negative health effects. Scientists have long warned that air pollution increases the risk of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases and reduces life expectancy.

The air in Milan (Italy) on a polluted day with lots of PM 2.5 fine dust. Photo: ANSA

“Current levels of air pollution put many people at risk of health problems and disease, and we know that reducing air pollution levels will reduce these numbers,” said Mark Nieuwenhuijsen, director of the Barcelona Institute for Global Health (ISGlobal).

So exactly how bad is air pollution in Europe? To shed light on this question, German newspaper DW teamed up with the European Data Journalism Network to analyze satellite data from the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS).

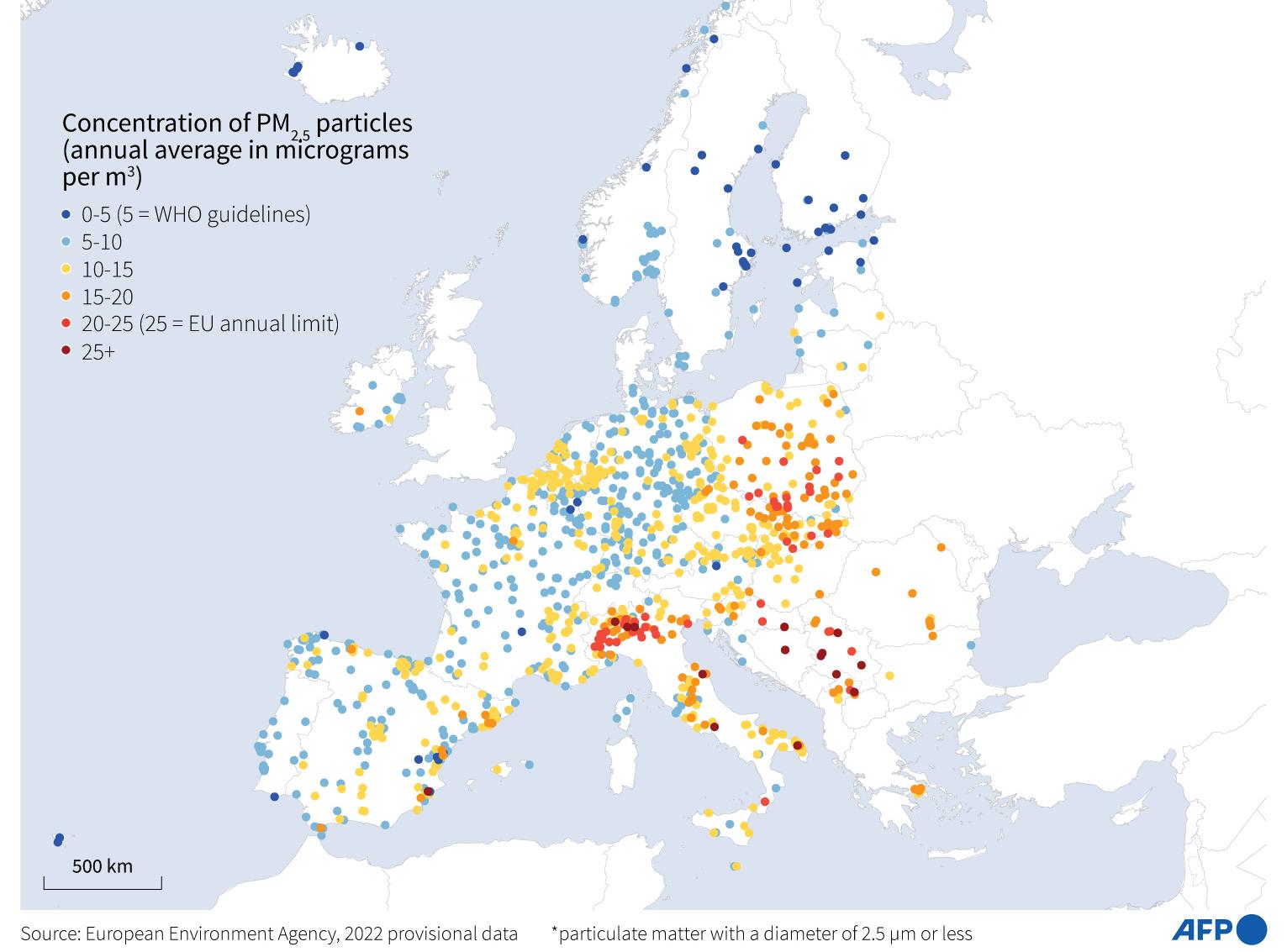

DW's analysis shows that by 2022, most people in Europe – around 98% of the population – will live in areas where concentrations of fine particulate matter, often abbreviated as PM 2.5 – exceed the limits set by the WHO.

WHO recommends that the average annual concentration of fine particle pollution should not exceed 5 micrograms/m3 of air (for reference, a microgram is a thousand times smaller than a milligram).

Pollution levels vary across Europe. It can be particularly severe in parts of Central Europe, the Po Valley in Italy, and larger urban areas such as Athens (Greece), Barcelona (Spain) and Paris (France). DW's analysis found that the most polluted areas in Europe have average annual PM 2.5 concentrations of around 25 micrograms per cubic meter.

High levels of air pollution in individual European cities have been reported before, but this new data analysis provides the first continent-wide comparison of pollution levels. It shows where air quality has improved and where it has worsened.

DW also used the data to identify two locations with similar problems but different trends. In northern Italy, pollution levels are high and appear to be staying that way. In southern Poland, pollution levels are also high but appear to be decreasing.

This result raises questions about air pollution reduction strategies in countries, when the effectiveness of climate policies does not always happen as expected by planners.

Different determination, different results

To shed more light on this conclusion, let's take a closer look at the first case mentioned in the DW report: northern Italy.

Air quality has been consistently poor in northern Italy. In mid-February 2023, many cities in Italy’s Po Valley were awash with pollution. The Lombardy and Veneto regions were particularly affected. According to Copernicus researchers, average daily PM 2.5 concentrations in cities such as Milan, Padova and Verona rose above 75 micrograms per cubic meter.

Map of PM 2.5 dust concentration in Europe in 2022 provided by AFP, with units of micrograms/m3 of air. Photo: AFP

Geography is partly to blame: The area is surrounded by mountains, and pollution from heavy traffic, industry, agricultural emissions and smog from residential heating is trapped in the valleys.

Environmental agencies report that thousands of people in the region die prematurely each year from pollution-related illnesses. A study published in the prestigious scientific journal The Lancet, using pollution data from 2015, estimated that about 10% of deaths in cities like Milan could be prevented if average PM 2.5 concentrations were reduced by about 10 micrograms per cubic meter.

If major European cities could meet the 5 microgram/m3 target, the researchers concluded there would be 100,000 fewer pollution-related deaths each year.

But that is not the direction the Po Valley is heading. “In addition to the negative geographical situation, we are doing the exact opposite of what we should be doing,” says Anna Gerometta, lawyer and president of Cittadini per l’Aria. Gerometta argues that restrictions on emissions from cars, home heating systems and meat factories are too weak.

In Poland, however, local strategies are showing results. The country has now phased out coal furnaces in an effort to improve air quality. Pollution levels in many parts of Poland are among the highest in Europe, but they have been falling steadily since 2018.

The progress comes after the Polish government launched a plan to modernise household heating systems, a process that has been underway for 10 years. “We call household heating systems ‘smokers’ because they produce so much smoke,” said Piotr Siergiej, head of the Polish environmental organisation Smog Alert. “Nearly 800,000 have been replaced, but there are still around 3 million waiting to be replaced.”

In the Krakow region, where a ban on burning coal and wood for indoor heating came into effect in 2019, most of the old heaters have already been replaced.

Perceptions are changing

Air quality in Europe is generally better than in other parts of the world . For example, in northern Indian cities such as New Delhi, Varanasi and Agra, average PM 2.5 values can reach as high as 100 micrograms/m3. In Europe, DW data shows the highest pollution levels are 25 micrograms/m3.

But even at relatively low levels, air pollution can have a significant impact on human health. New European air quality regulations will allow an annual average concentration of 10 micrograms of fine particles per cubic meter of air.

Pollution in Europe is of particular concern to people here. Photo: Getty

The European Parliament's Environment Committee has proposed adopting the WHO's recommendations more strictly, at 5 micrograms of fine particles per cubic meter of air. But even at 10 micrograms, the European limit is still stricter than current standards in most countries around the world, which allow annual PM 2.5 concentrations of 20 micrograms per cubic meter - four times higher than the current WHO recommendation.

Health researchers and environmentalists say new European air quality regulations will mirror WHO guidelines but ensuring the new standards are met will be a major challenge.

“The EU restrictions are not only about health but also about economic arguments, [while] the WHO restrictions are made by experts who only take into account health,” said Mark Nieuwenhuijsen, director of the Barcelona Institute for Global Health. “I hope the EU will go along with the WHO, even though some may think it is too expensive.”

Nieuwenhuijsen is pessimistic. But things are changing. According to the 2022 Eurobarometer survey, a majority of Europeans consider respiratory diseases caused by air pollution to be a serious problem today. While many respondents said they were not fully informed about current standards, they all thought air quality regulations should be strengthened.

Khanh Nguyen

Source

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh chairs the 16th meeting of the National Steering Committee on combating illegal fishing.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/07/1759848378556_dsc-9253-jpg.webp)

![[Photo] Super harvest moon shines brightly on Mid-Autumn Festival night around the world](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/07/1759816565798_1759814567021-jpg.webp)

Comment (0)