On August 23, 1973, Swedish fugitive Jan-Erik Olsson walked into the Sveriges Kreditbank in Stockholm's Norrmalmstorg Square shortly after it opened. He was disguised with a woman's curly wig, blue sunglasses, a black mustache, and rosy cheeks. Olsson fired a submachine gun into the ceiling and shouted in English, "Let the party begin!"

Things got weird from there.

When Olsson entered the bank, the employees who became his hostages felt nothing but fear. "I believed a madman had entered my life," said Kristin Enmark, a 23-year-old bank employee at the time.

But the hostages’ terror didn’t last long. In fact, over the course of the six days of the robbery, a surprising bond formed between the robber and the four hostages, three women and one man. It eventually gave birth to a new psychological term: Stockholm Syndrome.

Olsson was serving a three-year sentence for burglary. In early August 1973, the prison allowed Olsson to be released for a few days for good behavior, on the condition that he report back at the end of his sentence. Olsson did not return, but instead planned a daring robbery.

Instead of robbing the bank, Olsson took the young employees hostage and made demands of the police. He wanted 3 million Swedish kronor (about $710,000 at the exchange rate at the time) and a getaway car. In addition, to support his plan, Olsson also wanted the police to hand over his former cellmate Clark Olofsson, who was notorious throughout Sweden for his series of bank robberies and multiple prison breaks.

Olsson gambled that " the government would not risk refusing the request and risking the murder of women," writes author David King in his book 6 Days in August: The Story of Stockholm Syndrome. "Not in Sweden. Certainly not that year, when the prime minister faced a tight election."

So, as snipers surrounded the building, Olsson retreated into the bank vault with the hostages, leaving the door ajar and waiting for his demands to be met.

Enmark was held handcuffed along with two colleagues, teller Elisabeth Oldgren, 21, and Birgitta Lundblad, 31, the only hostage who was married with children.

Initially, Olsson's calculations were correct. The authorities transferred the money, a blue Ford Mustang, and Clark Olofsson arrived at Kreditbank later in the day. Olsson planned to drive away with the money, Clark, and several hostages, then flee Sweden by boat.

But the police had retained the keys to the Mustang. Olsson and his group were trapped.

Enraged, Olsson yelled and threatened to kill those who intervened, even shooting a police officer in the arm. But Clark's appearance calmed those inside the bank.

“When I arrived, they were terrified,” Clark said in 2019. “After five minutes, they calmed down. I told them, ‘Hey, calm down, we’ll handle this.’” Clark untied the three women and walked around the bank to assess the situation, finding another employee, 24-year-old Sven Safstrom, hiding in the storage room. Safstrom became the fourth hostage.

Clark brought a bank phone into the vault so the hostages could call their families. When Lundblad cried because she couldn't reach her husband and children, Olsson touched her cheek and gently said, "Try again, don't give up."

Day two

On August 24, 1973, after the first night in the vault, Oldgren felt claustrophobic, so Olsson cut a length of rope, tied it around her neck, and let her walk around the bank. He also put his coat around her shoulders as she shivered from the cold.

Olsson grew increasingly frustrated with the slowness of the authorities' actions. Olsson convinced Safstrom to let him shoot him in the thigh in front of the police as a threat. Olsson promised that the shot would only graze. "Just the leg," Enmark told Safstrom by way of encouragement.

Safstrom accepted, but Olsson ultimately did nothing. "I still don't know why the plan didn't work. All I remember is thinking how kind he was to promise to only shoot me in the leg," Safstrom said.

Meanwhile, crowds gathered in Norrmalmstorg square outside the bank, and the media continued to report on the events, interviewing hostages and their captors by phone.

At around 5 p.m., Enmark spoke to Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme, and radio and television stations also broadcast their conversation. She asked Prime Minister Palme to allow Olsson to leave the bank and drive away with the money. Enmark volunteered to go along as a hostage.

"I had complete trust in Clark and the bank robber. I wasn't desperate. They hadn't done anything to us," Enmark said. "On the contrary, they were very kind. What I was afraid of was that the police would attack and get us killed."

Swedish leaders refused, saying that letting bank robbers out on the streets with weapons would endanger the public.

Olsson's disguise worked. Police mistakenly identified him as another escapee Clark knew, Kaj Hansson. They even brought in Hansson's younger brother, Dan, to try to talk the robber down, but only received gunshots. Police asked Dan to call the phone in the vault.

Dan hung up after speaking to Olsson and called the police "idiots." "You have the wrong man!" he shouted.

Third day

On the morning of August 25, police tried a more daring solution. An officer sneaked in and closed the vault door, trapping the hostages inside with Olsson and Clark. For those in the vault, the door had been left open so that police could provide food and drink, and through it, Olsson could hope to escape. That hope was gone.

Authorities jammed phone signals, preventing those inside the vault from calling anyone except police, fearing media access to the robber might inadvertently endear him to the public.

Nils Bejerot, a psychiatrist consulted by police, assessed that a "friendship" may have formed between the robber and the hostages. Police hoped that this might prevent Olsson from harming the hostages.

In fact, such links had already formed and the police did not foresee how strong they would be.

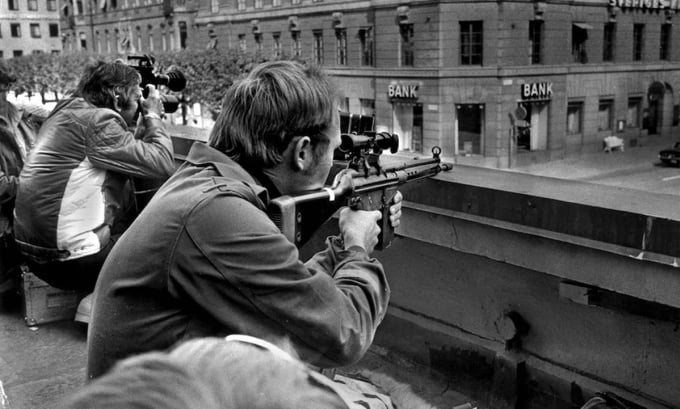

A reporter and a police sniper sit side by side on the roof opposite Sveriges Kreditbank, on the second day of the robbery. Photo: AFP

In the afternoon, not knowing when he would be given food, Olsson pulled out three pears left over from the previous meal, cut each in half, and gave each person a portion. Everyone noticed that Olsson took the smallest piece. “When he was treated well, we treated him like a god,” Safstrom said.

When she slept at night, Enmark could hear people breathing and know when they were in sync. She even tried to change her own breathing to match. “That was our world ,” she said. “We lived in the bunker, breathing and existing together. Anyone who threatened that world was our enemy.”

Wednesday and Thursday

On August 26, the sound of drilling caused chaos in the group.

The police told Olsson they were making a hole big enough for him to surrender his weapon. It took hours to drill through the steel and concrete ceiling. Those in the bunker thought about the real reason for doing this: Pumping tear gas to force the robber to surrender.

In response, Olsson placed the hostages under the hole with nooses around their necks, the ropes tied above a row of safe deposit boxes. He told police that if any gas knocked the hostages unconscious, the nooses would kill them.

“I don’t think he’s going to hang us,” Enmark said in 2016. But the hostages were worried about what the gas would do to them. Olsson told them that after 15 minutes of exposure to tear gas, they would all suffer permanent brain damage.

The police began drilling more holes above the vault. They sent a bucket of bread down the first hole, the hostages' first real meal in days, giving them a brief respite. As they began to tire, Olsson took turns putting nooses on each of them. Safstrom asked the robber if he could put the noose on all of the hostages.

“Safstrom is a real man,” Olsson told the New Yorker. “He’s willing to be a hostage for other hostages.”

The last day

By the sixth day, the crew had drilled seven holes in the vault ceiling, and as soon as the last hole was completed, gas began to pour in. The hostages fell to their knees, coughing and choking before Olsson could order them to re-thread the noose around their necks. Soon, police heard shouts of, “We surrender!”

After opening the door, the police ordered the hostages to leave first, but they refused, fearing that Olsson and Clark would be killed by the police. Enmark and Oldgren hugged Olsson, Safstrom shook his hand, and Lundblad told Olsson to write a letter to her. The robber and his accomplice then left the bank vault and were arrested by the police.

Olsson served 10 years in prison and was released in the early 1980s. Clark was convicted in the district court but later acquitted in the Svea Court of Appeal. Clark maintained that he had cooperated with police to protect the hostages. He was sent back to prison to serve the remainder of his previous sentence and was released in 2018.

From this event, Dr. Bejerot used the name "Normalmstorg syndrome" to describe the phenomenon of abductees developing feelings for their captors. The term was later changed to "Stockholm syndrome".

Professional associations do not recognize it as a form of psychological diagnosis, although it has been invoked in some cases of abuse against prisoners of war and most notably in the kidnapping of Patty Hearst, a year after Olsson's robbery. Hearst, the niece of an American billionaire, developed sympathy for her captors and joined the gang.

Some experts question whether it is a psychological disorder or simply a survival strategy in the face of extreme danger. Law enforcement experts in the United States say the phenomenon is rare and over-reported in the media. But it still appears frequently in popular culture, including books, movies and music.

Enmark, who left the bank and became a psychotherapist, said in 2016 that the hostages' relationship with Olsson was more self-protective than a syndrome.

"I think people blame the victim," she said. "Everything I did was a survival instinct. I wanted to survive. I don't think it's that weird. What would you do in that situation?"

Vu Hoang (According to Washington Post )

Source link

![[Photo] Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh launched a peak emulation campaign to achieve achievements in celebration of the 14th National Party Congress](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/5/8869ec5cdbc740f58fbf2ae73f065076)

![[Photo] Bustling Mid-Autumn Festival at the Museum of Ethnology](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/4/da8d5927734d4ca58e3eced14bc435a3)

![[VIDEO] Summary of Petrovietnam's 50th Anniversary Ceremony](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/4/abe133bdb8114793a16d4fe3e5bd0f12)

![[VIDEO] GENERAL SECRETARY TO LAM AWARDS PETROVIETNAM 8 GOLDEN WORDS: "PIONEER - EXCELLENT - SUSTAINABLE - GLOBAL"](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/402x226/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/7/23/c2fdb48863e846cfa9fb8e6ea9cf44e7)

Comment (0)