Experts say the Hawaii wildfire disaster is the result of many factors that have long existed in the archipelago and have precedents.

After winds from a hurricane caused wildfires to spread across the Hawaiian Islands in 2018, researchers scoured the scientific literature for similar disasters. They found two.

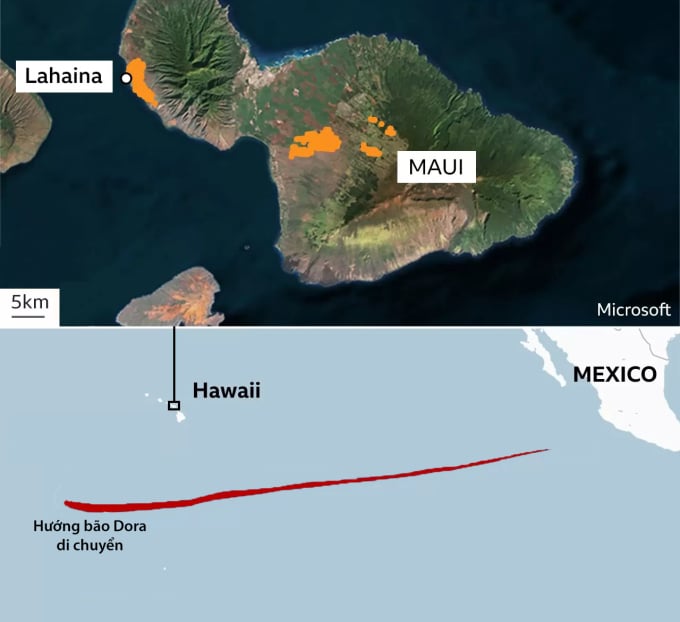

Now, hurricane-fueled wildfires are once again burning through the state, killing at least 80 people and leaving the historic town of Lahaina almost completely destroyed.

Scientists and wildfire activists say Hawaii's fires have been amplified by multiple factors and more disasters are likely in the future.

Elizabeth Pickett, co-director of the Hawaii Wildfire Response Organization, said that while the fires of the past week have taken many by surprise, they were not entirely unexpected. Despite its rainforests and waterfalls, Hawaii is a hot place, and temperatures are rising.

"We can't control everything, but this disaster was predictable," she said.

Smoke rises from a forest fire in Hawaii on August 10. Photo: AFP

The fires began spreading across Maui, Oahu and the Big Island of Hawaii on August 8, when the National Weather Service issued a red alert. Much of the state has been experiencing months of drought, especially the area surrounding the town of Lahaina.

That means even a small spark can quickly ignite a fire in vegetation already parched by the heat. And fueled by winds, the flames can spread toward residential communities.

Strong winds are common in Hawaii. Even in typical summer weather, winds can reach speeds of up to 40 mph. But the winds that have swept across the islands and fueled the fires this past week have been particularly strong, with gusts reaching more than 80 mph on both the Big Island and Oahu, and nearly 65 mph on Maui, according to data from the National Weather Service.

Some Hawaii officials admitted the extent of the fires caught them by surprise. "We did not expect that a hurricane that did not impact our islands could cause such devastating wildfires," said Lieutenant Governor Josh Green.

Location of Maui Island and path of Hurricane Dora. Graphics: BBC

The winds are believed to be the product of a difference in atmospheric pressure between an area of high pressure in the North Pacific and low pressure at the center of Hurricane Dora, which was hundreds of kilometers south of the Hawaiian Islands on August 8.

Even without Dora, the relatively dry winds that blow along Hawaii’s mountain slopes would have been enough to fuel the fires, said Alison Nugent, a meteorologist at the University of Hawaii. But Dora added to the intensity of the winds, she said.

Similar scenarios played out in two examples the researchers found. In 2007, a tropical storm fanned smoldering fires in Florida and Georgia. A decade later, fires across Portugal and Spain killed more than 30 people when a hurricane swept across the two countries’ coasts.

Nugent said there is every reason for scientists to worry that future hurricanes, while rarely making direct landfall in Hawaii but rather passing over it, could still cause serious damage to the islands.

While there is no clear link between human-caused climate change and drought in Hawaii, the general trend across the region is decreasing rainfall and increasing the number of consecutive dry days.

Ian Morrison, a meteorologist in Honolulu, Hawaii, said this year's rainy season brought below-average rainfall, meaning the weather became unusually dry as summer entered.

One factor that increases the risk of fires in Hawaii is the growth of non-native, flammable grasses. Like much of the rest of the islands, Maui’s native vegetation has been replaced by sugar and pineapple plantations and cattle ranching. However, in recent decades, agricultural activity has declined significantly.

Nugent’s research shows that before Hurricane Lane hit in 2018, 60% of Hawaii’s cropland and pastureland had been abandoned, replaced by flammable grasses like citronella and pampas grass, which were introduced to the islands to cover bare pastures and as ornamental plants.

Both species are adapted to thrive after fires, creating more fuel for subsequent fires and crowding out native plants.

“It’s like throwing a ton of weeds in your backyard and then planting some really delicate plants in between,” says Lisa Ellsworth, an associate professor at Oregon State University who has studied invasive grasses in Hawaii. “It’s a cycle that creates more invasive grasses and more wildfires.”

Researchers found that non-native flammable grass and shrublands accounted for more than 85 percent of the area burned in the 2018 Hurricane Lane wildfires. Local fire agencies estimate such areas now cover about a quarter of Hawaii.

Wildfire destroys Hawaii resort town. Video: Reuters, AFP

These vegetation patches often run along densely populated areas with valuable real estate, so Pickett says significant government investment and new policies are needed to help communities like these better prepare for the fire risks they face.

In addition to the damage to property and life, the effects of wildfires also damage Hawaii's landscape in the long term.

Unlike the western US, where moderate fires can improve forest health (cycling nutrients needed for plants), Hawaii's ecosystem is not adapted to coexist with wildfires, said Melissa Chimera, coordinator for the Pacific Fire Exchange, a fire prevention organization.

The burned native flora is replaced by invasive species instead of growing back. A 2007 fire destroyed almost all of the yellow hibiscus, Hawaii’s state flower, on the island of Oahu.

On the other hand, rains can also wash fire remnants into the ocean, suffocating corals and destroying water quality.

“For the ecosystem of the area, fire has no effect whatsoever,” Chimera said. “Absolutely none.”

Vu Hoang (According to Washington Post )

Source link

Comment (0)