Walking the Lines

Qatar's diplomacy in the Gaza war, including helping to broker a temporary ceasefire and hostage release that took effect on November 24, cemented the super-rich Muslim nation as Washington's preferred interlocutor with extremist groups and pariah states in the Middle East, and even around the world.

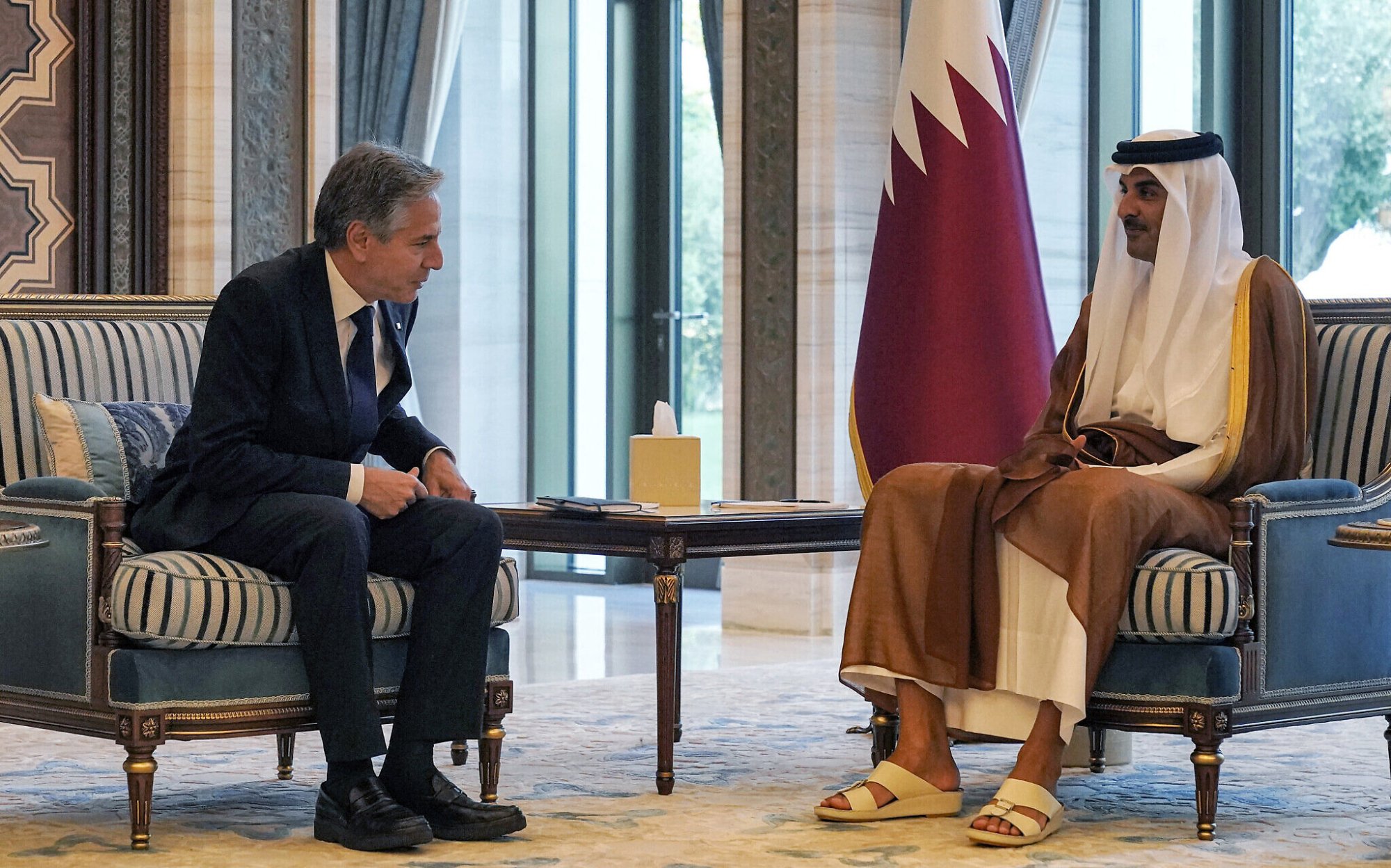

Qatar's Emir, Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, held talks with US Secretary of State, Antony Blinken to find a solution to the conflict in the Gaza Strip. Photo: Reuters

It’s a remarkable effort by Qatar, which began some 30 years ago, when the tiny Gulf monarchy sought to insulate itself among its larger neighbors by acting as a “broker” in resolving regional disputes while also gaining the trust of the United States and the West. Now, Qatar has also been home to a major U.S. military base for the past two decades and is a “big” customer for billions of dollars in weapons from the United States and Europe. The approach, of course, is fraught with risks, as Qatar’s willingness to negotiate with extremist groups has been recognized.

The past seven weeks of painstaking mediation, launched by Qatar hours after Hamas’s cross-border attack on Israel on October 7, have once again exposed those tensions. Some senior U.S. lawmakers and former officials, for example, have criticized Qatar as a key backer of Hamas, even as the Biden administration is pressing Qatar to help secure the release of hundreds of kidnapped civilians and soldiers.

Qatar opened a channel with Hamas leaders more than a decade ago, a move Qatari officials told the Wall Street Journal was at the request of the United States. Qatar later allowed the Palestinian militant group to open an office in Doha and provided hundreds of millions of dollars in aid to the Gaza Strip. Many in Israel are suspicious of Qatar's ties to Hamas and worry that it could hamper efforts to destroy it.

Firm line

But Qatari officials say they have grown accustomed to having their motives and integrity questioned over the years, and have become increasingly vocal in defending their positions.

“Qatar’s political leadership is willing to take risks” in maintaining contacts with parties shunned by the West, Majed Al Ansari, a foreign ministry spokesman and senior adviser to Qatar’s prime minister, said in a recent interview. “You can only get high returns by taking high risks, and that’s how we do these things,” Mr. Al Ansari added.

Qatar's strategy puts the Gulf state at particular risk, with its Arab neighbors cutting diplomatic and economic ties in 2017, and even considering launching a ground war against Qatar.

Hamas leader Ismail Haniyeh (left) also believes in Qatar's mediation role. Photo: Reuters

Saudi Arabia, Egypt and others have grown increasingly frustrated with Qatar's independent foreign policy, which has included support for Muslim Brotherhood affiliates and revolutionary movements in the Arab Spring uprisings that toppled longtime autocrats across the region.

The diplomatic rift and economic boycott ended after three years without any meaningful concessions. Shaken but defiant, Qatar instead redoubled its efforts to mediate some of the world’s thorniest conflicts, positioning itself as a “neutral arbiter.”

“The Qataris will do everything in their power to be indispensable partners to the United States. That is the cornerstone of Qatari foreign policy,” said Patrick Theros, a former U.S. ambassador to Qatar. “That also means sometimes keeping a clear distance from the United States, because then they can talk to the other.”

At the end of the 20-year US war in Afghanistan, it was Qatar that hosted peace talks with the Taliban. The Islamist militants opened an office in Doha in 2013 at the request of the US, seeking to reduce the influence of Pakistan's intelligence agency over them.

When the Western-backed Kabul government collapsed in August 2021, Qatar helped evacuate tens of thousands of people from the country, including US citizens and Afghans who had worked with the US military. They remain key emissaries for the Taliban, an organisation the US considers a terrorist group.

Qatar has maintained channels with the Kremlin since Russia launched its military offensive in Ukraine last year. At the same time, it has hosted US talks with Venezuela on lifting sanctions in exchange for political change.

Weeks before the Gaza war broke out, five Americans freed from Iranian prison landed in Doha en route to the United States as part of a Qatar-brokered deal to release $6 billion in Iranian oil revenues and restart nuclear talks. After Hamas’s attack on Israel last month, the United States and Qatar agreed to block Iran’s access to the funds amid concerns about Tehran’s long-standing funding for Hamas.

“Qatar is turning itself into a prickly Switzerland,” said David Roberts, author of a book on Qatar’s security and development policy in the Gulf, pointing to Doha’s efforts to maintain neutrality while arming itself heavily against external threats.

Advantages of small countries

With a native population of around 300,000, Qatar has not always been an obvious choice for international mediation. In the early 1990s, the impoverished former British colony, struggling to maintain its autonomy in the shadow of Saudi Arabia and Iran, refused to join a coalition of other coastal emirates.

After Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al Thani, the current emir’s father, came to power, Qatar began exploiting its control of much of the world’s largest natural gas field. It channeled the wealth it gained into building a military base for the US military, which had been driven out of neighboring Saudi Arabia, and establishing Al Jazeera, a pan-Arab television station that provided serious coverage of the region.

Qatar's efforts helped Israel and Hamas reach a temporary ceasefire and release hostages. Photo: NBC

Al Jazeera has helped create a distinctive image of Qatar and has become a very effective tool for extending the country's influence. Qatar's small size and low profile have given it a reputation as an honest broker. Its wealth has helped lubricate diplomacy, funding development programs in many countries where it has sought to resolve conflicts, and its small indigenous population has given the Qatari government relative freedom in foreign policy without having to worry much about domestic backlash.

For years, Sheikh Hamad bin Jassim Al Thani, Qatar's former foreign minister and later prime minister, flew around the Middle East trying to mediate disputes. Success came in 2008, when he helped broker a deal between factions in Lebanon that prevented another civil war there.

A few years later, Qatar agreed to host Hamas's exiled leadership after the group closed its office in Damascus, Syria, following the outbreak of the Syrian civil war. For years, the Qataris have funded electricity in Hamas-controlled Gaza and provided assistance to 100,000 of the poorest families there. Days before the October 7 attack, they negotiated an increase in Israeli work permits for Gaza residents.

“Why are we able to mediate so strongly and have open channels of communication between Hamas and Israel? It is because of the trust we have from both sides,” said Al Ansari, an adviser to the Qatari prime minister.

Source

![[Photo] Binh Trieu 1 Bridge has been completed, raised by 1.1m, and will open to traffic at the end of November.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/2/a6549e2a3b5848a1ba76a1ded6141fae)

Comment (0)