In the context of increasingly severe climate change, extreme rainfall and urban flooding have become a constant threat. In this situation, the “Sponge City” model is emerging as a sustainable solution, combining green infrastructure and ecological thinking to help urban areas absorb, retain and reuse rainwater.

Global Trends: From China to the World

Originating in China, the concept of “sponge city” was developed by landscape architect Kongjian Yu in the early 2000s. Accordingly, “sponge city” is an urban model designed to absorb, store and reuse rainwater like a sponge, instead of letting it overflow and cause flooding.

To achieve this, the city has applied many solutions such as increasing the permeable surface area with permeable materials for streets and sidewalks; integrating green infrastructure with flooded parks, rain gardens, ecological lakes, green roofs and walls; and building a system to store and reuse rainwater through underground tanks and smart channels.

In addition, modern technology such as IoT, water level monitoring sensors and early warning systems are also deployed for effective management. The ultimate goal is to turn the city into a smart ecosystem, adapt to climate change, reduce flooding and make the most of natural water resources.

Kongjian Yu makes a clear distinction between “grey” infrastructure – such as concrete embankments and underground sewers – and “green” infrastructure – such as wetland parks, ecological lakes, and rain gardens. According to Yu: “Gray infrastructure consumes energy and disrupts natural ecosystems. Meanwhile, nature-based ecological solutions are the key to protecting the environment and people.”

This model has been deployed in more than 250 cities in China, and is now spreading to urban areas such as New York, Rotterdam, Montreal, Singapore...

Optimizing nature, costs and community

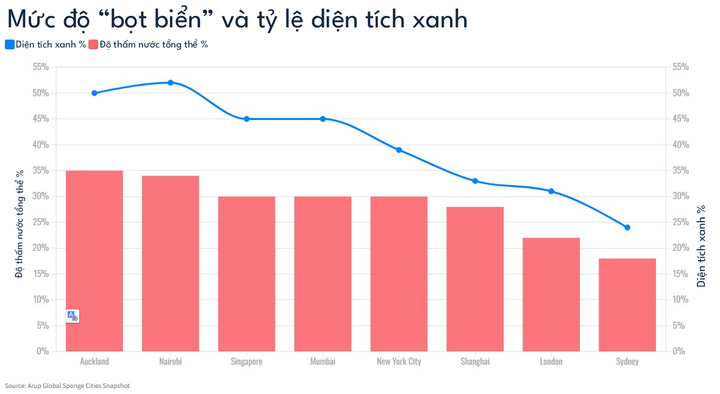

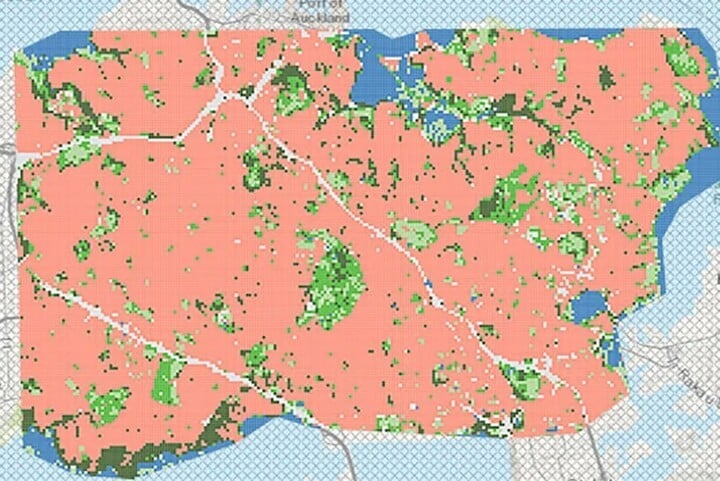

According to the report Global Sponge Cities Snapshot According to Arup, cities with more green space, permeable land and natural river ecosystems will find it easier to adopt this model. Tom Doyle, an expert at Arup, commented: “We want cities to see natural resources as infrastructure that needs to be protected and developed.”

The "sponge city" model brings many practical benefits to modern cities.

First, the ability to absorb rainwater helps reduce flooding, especially during heavy rains caused by climate change. In addition, green spaces such as wetland parks, rain gardens and ecological lakes contribute to urban cooling, improving air quality and creating a healthier living environment for residents.

The enhancement of greenery and natural ecosystems also promotes biodiversity, while providing a friendly community living space. Notably, compared to traditional concrete infrastructure solutions, this model helps save long-term costs by reducing maintenance costs, increasing the life of the project and limiting damage from natural disasters.

Difficult to deploy in highly urbanized areas

Despite bringing many benefits in terms of environment, economy and resilience to climate change, the implementation of the “sponge city” model still faces many practical challenges.

One of the major challenges is limited space and land ownership, especially in developed cities like New York or London, where high density and expensive land prices make expanding green space difficult. According to expert Tom Doyle, despite thousands of green solutions being applied in areas like Brooklyn and Queens, they are still not enough to compensate for the huge amount of existing impermeable space.

In addition, geological and soil characteristics also significantly affect the effectiveness of the model. For example, Nairobi, although having a large green area, is mainly clayey, which makes the water permeability lower than Auckland, which has sandy soil that drains easily.

In addition, the pressure of urban development with increasing demand for housing and infrastructure often overwhelms the space for nature, reducing the “spongeiness” of the city. Finally, the initial investment cost for building or renovating green infrastructure is not small, requiring interdisciplinary coordination between urban planning, environment, finance and community – a challenge that is not easy to overcome in actual implementation.

Lessons from Denmark: From disaster to pioneer

Amidst these opportunities and challenges, Copenhagen – the capital of Denmark – has proven that a city can completely transform itself into a “sponge city”, if it has vision and determination.

On July 2, 2011, an extreme rainstorm – considered “once in a millennium” – hit Copenhagen – the capital of Denmark in just two hours, causing nearly $2 billion in damage. This disaster became a wake-up call, prompting the city to carry out a comprehensive reform of urban infrastructure, moving towards the “sponge city” model.

Instead of continuing to expand the traditional sewer system, Copenhagen has chosen to redesign public spaces to absorb and store rainwater. One example is Enghaveparken, which was renovated to store the equivalent of 10 Olympic swimming pools in underground tanks. These improvements not only reduce the risk of flooding, but also create urban amenities such as landscaped lakes, playgrounds and water sources for gardening.

The Copenhagen approach includes:

- Redesign parks and green spaces into water storage.

- Combine green infrastructure with modern engineering, such as underground reservoirs, water channels and early warning systems.

- Integrating urban planning with climate strategy, ensuring long-term sustainability and resilience.

According to According to the World Economic Forum , Copenhagen is now considered one of the global pioneer cities in applying the “sponge city” model as a strategy to adapt to climate change.

According to expert Floris Boogaard from Hanze University (Netherlands), we have the technology, what we need to do is will and determination: “Engineering is possible for everything – from floating houses to water storage systems – but what is important is political will and social consensus.”

The sponge city is not only a technical model, but also a new urban planning philosophy – where people live in harmony with nature, instead of trying to control it. In the future, cities that want to be resilient to natural disasters need to transform from “concrete” to “green”, from confrontation to adaptation.

Source: https://baolangson.vn/thanh-pho-bot-bien-giai-phap-do-thi-xanh-chong-ngap-lut-toan-cau-5060600.html

![[Photo] Binh Trieu 1 Bridge has been completed, raised by 1.1m, and will open to traffic at the end of November.](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/10/2/a6549e2a3b5848a1ba76a1ded6141fae)

Comment (0)