The global fisheries employ an estimated 27 million people. These workers, mostly from developing countries, accept difficult working conditions for minimum wages. Migrants are often deprived of even the minimum wage and are subject to physical and psychological violence.

In 2016, the international news agency Associated Press revealed the extent of modern slavery and human rights abuses at sea. An 18-month investigation led to the release of 2,000 “slaves” in Southeast Asia, some of whom were kept in cages and routinely tortured.

Since then, government agencies, commercial and non-governmental organizations around the world have joined forces to curb crime in this area. Today, modern technologies are beginning to play a central role in identifying violators.

GPS positioning and transceiver on board

The nonprofit SkyTruth supported the Associated Press investigation into “slavery at sea.” Its technology is based on the Automatic Identification System (AIS), a surveillance system installed on all passenger ships over 300 tons traveling internationally and cargo ships over 500 tons.

Today, more than 200,000 vessels regularly broadcast their location via transponders – radio signals. In 2016, SkyTruth launched the Global Fishing Watch platform – a website that tracks transponder signals to create the world’s first global commercial fishing map. Global Fishing Watch is free and available to everyone.

The platform works by analyzing information from AIS – essentially GPS data about a vessel’s location. Users can learn how and where a vessel is moving, determine how long it has been at sea, and whether it is transmitting data about itself – meaning whether it is a transparent link in the fishing industry. If there is no data or suspicious data appears, observers will trigger mechanisms to check the vessel.

Satellite surveillance and artificial intelligence

Even before satellite tools became widely available, human trafficking activist and observer Valerie Farabee tracked court actions through open sources and NGO reports. She regularly scanned Southeast Asian news outlets for news of human rights abuses at sea. “I looked for boats that were operating too long, fishing near protected areas or areas they weren’t supposed to be in,” said Valerie Farabee.

Valerie Farabee sees these characteristics frequently on vessels accused of forced labor and illegal fishing, where the workers are often vulnerable and desperate for work to feed their families.

At the time, Gavin McDonald, a data scientist at the University of California, was also looking into the suspicious behavior of such fishing vessels. He noticed that fishing vessels in remote areas were making suspiciously large sums of money.

“Given the types of goods they are catching, how much they are paying their crews and how much they are running, they cannot possibly be making that much revenue,” says Gavin McDonald. He speculates that forced labor is what allows these vessels to enter new fishing grounds cheaply, as coastal fishing routes have been depleted and there is nothing left to catch there.

Valerie Farabee helped Gavin McDonald identify boats that were being held for human rights violations. Analyzing the behavior of 23 vessels in the Global Fishing Watch database, Gavin McDonald identified 27 different types of criminal behavior. For example, such vessels spent more time at sea than others, used more powerful engines, avoided ports, fished longer, and made less frequent voyages. The length of time without an AIS signal from these vessels was also out of the norm.

Gavin McDonald then used predictive modeling to identify patterns in the data and machine learning to find other maritime criminals. He found dangerous behavior in 26% of the 16,000 fishing vessels in the Global Fishing Watch database. These vessels employ between 57,000 and 100,000 workers, many of whom may be victims of forced labor.

Satellite images

An avid boater and ocean lover, billionaire philanthropist and entrepreneur Paul Allen has been tackling complex maritime issues for years. His Vulcan Skylight program identifies “dark” vessels that do not transmit AIS signals using satellite imagery. These images capture fishing boats near marine reserves or objects refueling fishing boats.

Norwegian company Trygg Mat Tracking is using satellite imagery to track violators changing the names and flags on their vessels.

The role of satellite imagery in identifying “black” fleets was also demonstrated in a study of the waters between South Korea, Japan and Russia by Global Fishing Watch.

Images from Planet's Dove and SkySat satellites show that between 2017 and 2019, more than 1,500 vessels illegally caught more than 160,000 tonnes of squid in the Pacific Ocean, worth more than $440 million. This has caused squid stocks in the region to decline by 80% compared to 2003.

Global Fishing Watch attributes this to increased satellite monitoring and the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. Similar activity is being actively carried out in Russia. To better control domestic fisheries, the Russian company Sitronics Group plans to launch 70 satellites equipped with AIS receivers by 2025.

(according to RBC)

Source

![[Photo] General Secretary To Lam, Secretary of the Central Military Commission attends the 12th Party Congress of the Army](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/30/9b63aaa37ddb472ead84e3870a8ae825)

![[Photo] Solemn opening of the 12th Military Party Congress for the 2025-2030 term](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/30/2cd383b3130d41a1a4b5ace0d5eb989d)

![[Photo] The 1st Congress of Phu Tho Provincial Party Committee, term 2025-2030](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/30/1507da06216649bba8a1ce6251816820)

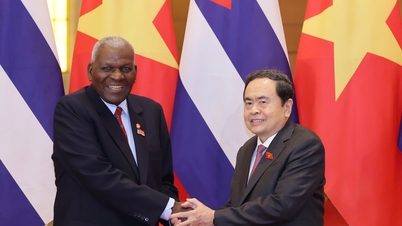

![[Photo] President Luong Cuong receives President of the Cuban National Assembly Esteban Lazo Hernandez](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/30/4d38932911c24f6ea1936252bd5427fa)

![[Photo] Panorama of the cable-stayed bridge, the final bottleneck of the Ben Luc-Long Thanh expressway](https://vphoto.vietnam.vn/thumb/1200x675/vietnam/resource/IMAGE/2025/9/30/391fdf21025541d6b2f092e49a17243f)

Comment (0)